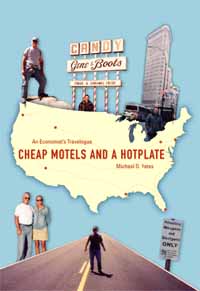

CHEAP MOTELS AND A HOT PLATE: An Economist’s Travelogue by Michael D. Yates BOOK TOUR BUY THIS BOOK |

I read Mike Yates’ new book Cheap Motels and a Hot Plate while overnighting in several low-end hotels on assignment for my union. I finished it as I laid in one of them just 200 yards down the road from the western Pennsylvania candy store featured on the cover. A couple of years ago, I calculated that, because of my trade union work, I had lived the equivalent of four years of my life in “cheap” hotels. With that under my belt, I thought to myself before reading the book: Mike Yates was going to have to come up with something pretty interesting to write a whole book about the America of cheap motels. He has.

Accompanied by his saint-for-a-wife Karen Korenoski, Mike embarked on the driving odyssey detailed in this book after an opportune retirement, some careful planning, and a healthy urge to get moving in search of better climes and greener pastures. Being from the Pennsylvania rustbucket myself, I understood completely Mike’s desire to hit the road and see the country. Or, frankly, to see anything other than the increasingly ramshackle towns of our home state. Pennsylvania has been economically hit hard over the past decades, and the death agony continues without letup.

His description of Pennsylvania Route 22 — “a dismal and depressing stretch of highway” — couldn’t be more accurate. I regularly drive Route 22 on union business, and it’s hard for me to think that Mike commuted along this corridor day after day, year after year, as he drove from his home in Pittsburgh to this teaching job in Johnstown to the east. No wonder he felt the need to pull up stakes and see what was over the next hill; it’s a normal reaction to the sad sights as only the Route 22 portion of the Keystone state can display them. And yes, there really is a drive-through go-go joint on that highway. You can’t make this stuff up.

Five years of motorized wandering back and forth across the U.S.A. are chronicled in this volume in a seemingly random yet actually coherent fashion. It’s much more than just a “this-is-what-we-saw-there” travelogue. It truly is “An Economist’s Travelogue” as the cover attests. More precisely, it’s a “Leftwing Economist’s Travelogue.”

Free from the bondage of family and work responsibilities, Mike and Karen roamed from one adventure to the next, working here, resting there, hiking everywhere, and taking in the full experience of our vast and diverse country. They stopped off in places as different as Yellowstone National Park and midtown Manhattan. As diverse as Portland, Oregon, Miami Beach, Florida, and several hundred places in-between. Our national parks feature high on their list of places to linger and enjoy. Some stops were slightly upscale, others pretty primitive. They even stopped for that once-in-a-lifetime visit to a nudist beach, exhibiting a bravery beyond that of mortal leftists, for sure.

Mike and Karen logged thousands and thousands of miles behind the wheel, alternating multi-month stays with short stopovers just long enough to take in the local sights, get some exercise, and then pack up for the road again. Their itinerary had no particular rhyme or reason, save for the desire that struck them or the practical or family need that compelled them to pick their next destination. Freedom was gained only by the effort it took to pack up and select the next destination. Finding a new place to stay was as simple as dickering with a hotel desk clerk for a bargain rate, or likewise with an apartment agent about a slightly longer stay in town. All the hot plate needed was a working outlet and a half decent market nearby.

For all of its freedoms and liberation, however, this journey contains a cautionary note for all of us. Dispirited by the state of his profession and tired of the suffocating Pennsylvania routine, Mike took flight in search of something, anything, more satisfying than watching the next plant closing or grading the papers of another class of uninterested students. Nevertheless, throughout his travels, it is impossible for Yates to escape the self-evident reality that our entire country is under corporate assault and showing the strains of the attack, just like Pennsylvania. He alternates between landings in parts of the country being methodically ruined as rich folks invade and stops among cast-off workers left to scratch out an existence after the exodus of jobs and opportunities from their locales. Just around the next bend might be another stopover nirvana, or just a hideous roadside experience as only we can make them here in the U.S.A. It’s not so much traditional travelogue as a careening from one extreme to the other, in a country of extremes.

I appreciated the descriptions of the nice things about our fair country, too few as they were. But that’s not the author’s fault. I’m not going to blame Mike Yates for reminding me that too much of our nation has become a post-industrial slag heap of communities and people. Some may cringe at Yates’ revelations of these stark realities, but I was regularly reminded during my read of the good counsel of Paris Commune participant and historian Lissagaray who defended his History of the Commune from those who criticized it as too brazenly honest: “He who tells the people revolutionary legends, he who amuses himself therewith sensational stories, is as criminal as the geographer who would draw up false charts for navigators.” I am glad that Mike took this trip and told this story. It needs to be told. No false charts here. No legends, either.

Yates makes a special attempt to include mention of the workers and people he comes across in his journey. Everyone seems nervous about the future, if they even think about one. Most people are friendly, but too preoccupied with daily life to actually become friends. Life for most is hectic, without apparent meaning or purpose other than to get by on another paycheck. We live obliviously with mile after mile of roadside litter. . . . The environment is being polluted and wrecked everywhere. . . . There’s too much traffic. . . . Too much pollution. . . . Everybody works too hard, too long, for too little, if they have any work at all. In a lot of places, even those surrounded by a beautiful landscape, life for working people just plain sucks. The rich do fine — they just put up another condo and a sign to keep out anybody who might dare to tread on their grass or gravel. The system is working to perfection, for them: the workers are being impoverished, the bosses are getting richer, and the environment is devoured in the process.

It’s what Mike did NOT find in his travels, however, that is the biggest lesson of the entire book. With only minuscule exception, during the five-year experience chronicled, Mike almost never found workers or people organizing or fighting back. Small acts of individual resistance and defiance of our corporate and political masters here and there, but overall just about nothing on an organized basis. No unions getting organized. No committees forming to mount a political counterattack. Few workers bothering to stick up for themselves, even when subjected to humiliation and degradation by life and work, let alone sticking up for each other. Here and there he encounters bewildered liberals who seem uneasy at the downhill direction of our nation, but with the buffer afforded by a middle-class lifestyle they see no reason to get too upset. Another glass of wine will take care of this nightmare for those folks.

In short, Mike Yates found a country and its people suffering in the advanced stages of multiple degenerative diseases, societal, economic, political, and individual. Not a pretty sight. I’m glad that Mike and Karen went looking for something better, and happier yet that Mike wrote a book about it. They seem to enjoy their rootless status, despite the fact that they didn’t find very much political or labor activism, solidarity, or fellowship in their travels. Hell, they seem to have had a hard time finding anyone who had even heard about the class struggle, let alone deciding to participate in it. Shocking? I think not. Mike is dead-on right: something is wrong here. Very wrong. As leftists, we ought to ponder this sad state of affairs. Could it be that we have lost something of our own here? Or stopped trying to do something about it all? I sure think so. In a country that imposes such pain and indignities on working people, and at such expense to our natural world, we need to do better.

In the 1968 science fiction film classic Planet of the Apes, the final climax is set in motion when the marooned astronaut — played by Chuck Heston — finally makes good his escape from the clutches of his ape captors. The bewildered Heston has found himself on a planet where things just are not adding up, in more ways than one. He is certain that a break for freedom will deliver him the answers he seeks. But — at the very moment of Heston’s horseback getaway — the Orangutan leader issues a warning to the impatient spaceman in search of his destiny: “Don’t look for it . . . you may not like what you find.” Mike Yates took that dare and went looking. You’ll have to conclude for yourself whether what he found was what he wanted — or not — as he roamed about his own “Planet of the Yates.”

I heartily recommend this out-of-the-ordinary Monthly Review Press volume to all.

Chris Townsend is Political Action Director for the United Electrical Workers Union (UE).

|

| Print