Open class struggle is every capitalist ruler’s nightmare. As long as poor working people suffer in silence, business can continue as usual. Heads of state can go on pushing the buttons and pulling the levers of power according to plan with little interference from below.

There is a point in time, however, when the legions of the poor increase in number and begin to understand that their personal problems are really political issues. The day they decide to act on that realization marks the beginning of the nightmare for the ruling class.

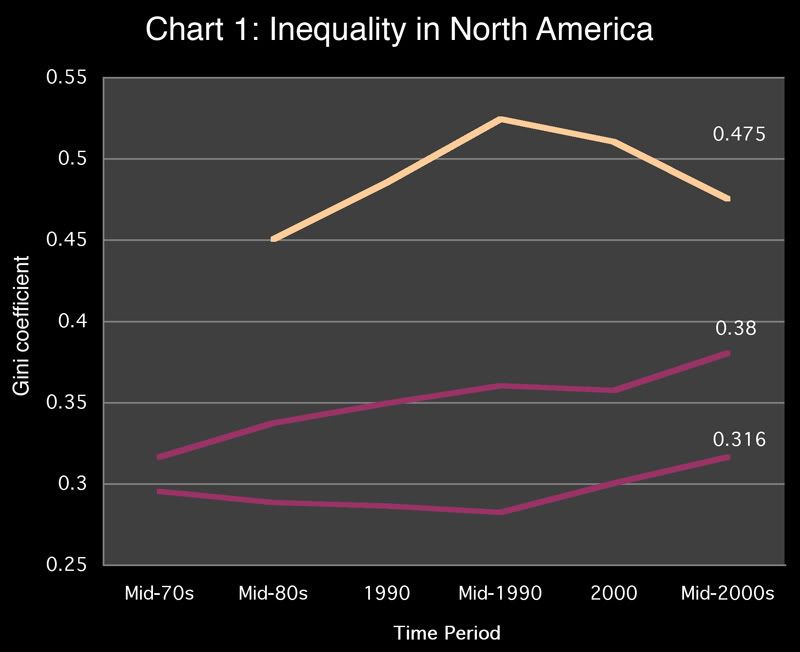

Mexico is on the threshold of such a qualitative change, and chart 1 explains why:

Chart 1 displays the trends of inequality in North America since the mid-1970s (the mid-80s for Mexico) by tracking the Gini coefficients for each country during the period. The Gini coefficient (the vertical axis of chart 1) is the most commonly used measure of income inequality within a nation. A low Gini coefficient indicates more equal income distribution while a high Gini coefficient indicates a more unequal distribution. 0 represents perfect equality (where every person has the same income) and 1 corresponds to perfect inequality (where one person has all the income in a society). The income measure used to calculate the Gini coefficients in chart 1 is disposable household income adjusted for household size.

Chart 1 indicates that income inequality in Mexico is by far the greatest in North America at 0.475 in the mid-2000s compared to 0.38 in the USA, and 0.316 in Canada. However, the most striking difference that emerges from a comparison of the national trends is the fact that inequality of household earnings fell significantly in Mexico in the decade following the passage of NAFTA. (The corresponding rise in inequality in Canada and the US reflects the flipside of the same phenomenon — the transfer of industrial jobs from the North to the South under the trilateral free trade agreement. Note that the trend of inequality in Canada was actually in decline until the advent of NAFTA.)

It must be kept in mind that despite the significant fall in income inequality in Mexico during the post-NAFTA decade, Mexico’s income inequality and poverty remains the highest in the over 100 countries monitored by the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Currently the average income of the poorest 10% of Mexican families is below US$1,000 in purchasing power compared to US$5,800 for poor families in the US.

Absolute poverty in Mexico also decreased during the post-NAFTA decade, yet 22% of all children and 30% of the population over 65 continue to live in households with income below the poverty threshold.

Calderon’s Nightmare

The trend of declining income inequality in Mexico under NAFTA depicted in chart 1 is the context, not the substance, of Mexican President Felipe Calderon’s nightmare.

After a decade of rising incomes and expectations, the impact of the current economic meltdown in the United States and Canada on Mexico will be all the more painful. Mexican workers will see the minimal gains that they made during the NAFTA decade wiped out with the prospect of much worse to come.

To be sure, the economic prospects for working people in Mexico are grim. The recession in the US and Canada has reduced the demand for goods and services produced in Mexico and decreased the need for Mexican workers in the North. Mexican emigration has dropped 42% over the last two years and remittances from the emigrant workers in the North that have kept many Mexican families and communities afloat are drying up rapidly.

The most that Mexican workers can expect for the future under the current regimes is the adoption of an austere guest worker program to legalize the exploitation of their labor. Such a program will aid economic recovery in the North but will do little for the workers themselves or for Mexico. (It must be noted that Calderon, like his predecessor Vicente Fox, avidly supports such a guest worker program.)

Despite the current plight of Mexican workers, NAFTA has been good for both capitalists in the North who have realized superprofits from the trilateral deal and the Mexican ruling class that have externalized their underdevelopment problems by both opening their depressed labor markets to foreign capitalists and by encouraging their unemployed to emigrate.

Renegotiating NAFTA could endanger the sweetheart deal between the ruling classes of the three nations.

Renegotiating NAFTA

During the Democratic primaries, Obama repeatedly criticized NAFTA, citing the million plus jobs that have been lost to the South and promising to renegotiate the deal. The implication that he will bring the work back to the US was a major factor in his election.

“It’s a bad idea,” Mexican Ambassador Arturo Sarukhan warned recently, “The probable endgame of that [renegotiation] is going to be the meltdown of what we’ve built over these last 15 years.”

Calderon’s nightmare is not chimerical. Mexico is already stressed by high unemployment and low wages, and a renegotiation of NAFTA could trigger a total collapse of the Mexican economy. In such an event, the trend of decreasing inequality in Mexico will reverse and inequality could surge to unprecedented heights. The most probable endgame of economic collapse is the resurgence of open class struggle in Mexico — Calderon’s nightmare come true.

Who knows? The celebration of a new Mexican revolution might coincide with the centennial of the first one.

Richard D. Vogel is a political reporter who monitors the effects of globalization on working people and their communities. Other works include: “The NAFTA Corridors: Offshoring U.S. Transportation Jobs to Mexico”; “Transient Servitude: The U.S. Guest Worker Program for Exploiting Mexican and Central American Workers”; “The Fight of Our Lives: The War of Attrition against U.S. Labor” ; and “How Globalization Works: Toyota Motor Manufacturing, Texas (TMMTX) — A Case Study.” Contact: <