When the global crisis of capitalism first broke out in 2008, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Erdogan said: “Hopefully, this crisis will touch Turkey like a tangent line.” Touched by the crisis, Turkey’s unemployment rate is already 15.5%, the highest in the history of the republic, the highest in Europe, and among the highest in the world. If that is only a tangential impact of the crisis, one wants to know what its central impacts will look like!

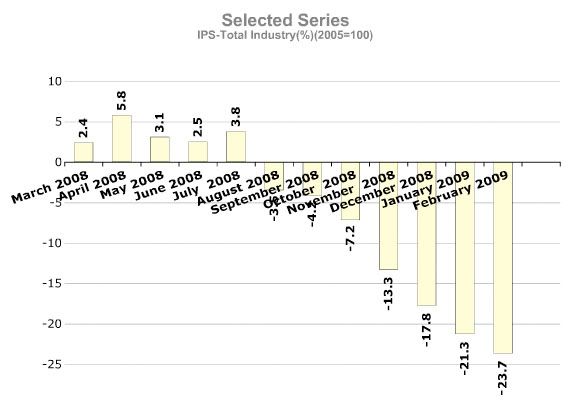

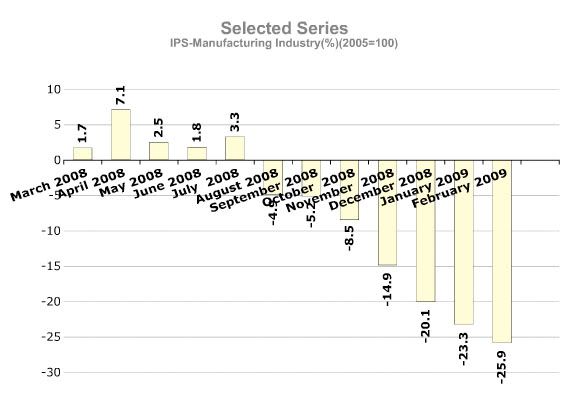

Let’s see the numbers: According to the findings of the Turkish Statistical Institute, the industrial sector in Turkey has sunk into a big recession. In February 2009, the Industrial Production Index decreased by 23.7%. The index for the manufacturing sector is even worse: a decline of 25.9% in February.

|

|

The capitalists in the banking sector, in contrast, are having little trouble — so far. In January-February of 2008, the total profit of this sector was 2,316 billion Turkish liras, but, in the same months of 2009, it was 3,204 billion Turkish liras — an increase of 38%. Prosperity of finance cannot but be ephemeral, however. How can bank loans be possibly paid back by the industry in the throes of such a deep recession?

According to the IMF’s latest World Economic Report, Turkey’s economy will contract by 5.1% in 2009. The Turkish oligarchy, especially the TUSIAD (Turkish Industrialists’ and Businessmen’s Association), is forcing the government to reach an agreement with the IMF. Any agreement with this imperialist institution will aggravate the effects of the crisis for the working class of Turkey. It will decrease the social expenditures of the municipalities, and the rate of unemployment will skyrocket.

Of course, such economic turbulences have their repercussions in the social and political arena. But the Turkish oligarchy is well prepared for another war on the people of Turkey. The organizations of the working class have already come under constant attacks by the state. For example, on the 25th of February, 20 members of two trade unions were detained in Sivas, a city in central Anatolia. They were accused, without any proof, of helping the members of illegal revolutionary organizations. The directors of these two unions were also arrested. Ten days later, on the 5th of March, a farmers’ union federation called Ciftci-Sen, comprising seven farmers unions, was closed by a court order. Opened in May 2008, this federation was to defend the rights of more than 15 million farmers in Turkey. Taking advantage of a legal loophole, the government shut down its activities. Five days later, on the 10th of March, police carried out a series of simultaneous operations against a trade union called Limter-Is, an independent newspaper called Atilim, and a democratic mass organization called the Socialist Platform of the Oppressed. (Limter-Is is the trade union organized to defend workers’ right to workplace safety after the workplace deaths of more than 90 workers in the shipyards of Tuzla.) A progressive weekly journal called Yuruyus was also subjected to censorship and confiscation.

But even these attacks couldn’t stop the development of workers’ resistance. To understand why, consider, for instance, a study done by the United Metal Workers Union (Birlesik Metal-Is): more than 500,000 people became unemployed between September and February, most of them in the Western part of Turkey. 180,000 of these newly unemployed workers had been working in the textile sector. Is it any wonder that strikes, factory occupations, and other forms of resistance started to flower all around the country, despite the oppression by the fascist state?

The resistance against the MEHA company, a textile company operating as a subcontractor of LCWaikiki, is one example of the growing resistance. The MEHA workers were compelled to perform unpaid overtime for nine months. The company kept forcing workers, under the threat of unemployment, to work for longer hours. On top of that, in November, January, and February, the company failed to pay the social insurance premiums of the workers. Therefore, in the beginning of March 2009, the workers decided to struggle to defend their rights. The company acted quickly and, with the help of the police forces, pushed 105 struggling workers out of the factory. They were fired.

Tens of MEHA workers, however, decided to carry on the resistance outside the factory. They set up tents and started to hold meetings — thus the MEHA resistance began. On the 18th of March, the company owner and the workers confronted each other. Again with the help of the police, the owner tried to move the textile machines to another place in order to evade the resistance. The workers tried to protect the machines but were faced with police brutality. So, on the 1st of April, workers adopted an innovative tactic of protest. They went to one of the LCWaikiki stores in Istanbul, took some shoes and clothes, and went up to the cashier. When it was time to pay, they declared that they didn’t have any money, because they were fired by a LCWaikiki subcontractor. They called for a boycott and talked with customers. Despite the threats by the company owner, the MEHA workers are still continuing their resistance.

Another resistance started in the Mersin International Port. The workers of a transportation company called AKAN-SEL decided to join a union called TUMTIS. On the 30th of December, the union declared that they were active among the AKAN-SEL workers. Six days later, 60 workers were suddenly fired because of their trade union membership. On the 6th of January, workers started the resistance. Despite the armed threats against the workers to force them to leave the union, they didn’t retreat. As the resistance mounted, the company fired more workers, more than 100 in total. The Mersin dock workers’ resistance has continued for months, and the number of the activist workers has reached 124.

The Sinter resistance is another recent example. Workers of the Sinter Metal Factory tried to get organized under the United Metal Workers Union, but when the company owner heard about this, he fired 480 organized workers. The workers at once started factory occupation on 22 December 2008. After two days of occupation, the resistance moved to the outside. Despite the winter cold, hundreds of workers kept resisting inside the tents. On the 2nd of April, the 100th day of the resistance, the workers held a celebration. They said, “We can resist for another 100 days until we win!”

One of the latest examples of resistance came from Mersin again. After four months of collective bargaining with the Toros Agricultural Company, the Petrol-Is trade union workers decided to strike. 262 workers refused to accept the proposed contract, which did not include any wage increase for two years.

These are only a few examples of the recent worker responses to the crisis.

May Day of Turkey’s Working Classes

Currently, the trade unions and the revolutionaries are preparing for May Day. International Worker’s Day is more than a celebration in Turkey. It is the day when the neo-colonial state forces’ clubs and tear gas are met with the bare hands of the people. For the last three years, the workers in Turkey have been struggling to celebrate their May Day in İstanbul Taksim Square. The square has its historical significance in the history of the Turkish working classes: it was the site of a mass murder carried out by the paramilitary forces of the state on May Day of 1977. 36 workers were killed by “unknown” gunmen on that day, now known as Bloody May Day. Since then, all the public demonstrations in Taksim Square have been banned, and no party or group has been allowed to enter the square for demonstrations, except the police forces.

However, beginning in 2007, the workers have been struggling to reclaim Taksim Square, so every May Day is now like a war fought between the state and the workers. This year, steeled by the anger born of the crisis, our working-class brothers and sisters will again come face to face with their old historical enemy: the face of the bourgeoisie as embodied in the gas masks of the special riot police.

Eren Buglalilar is an MA student in the Department of Sociology at the Middle East Technical University. Email: <tolstoyevski@gmail.com>.