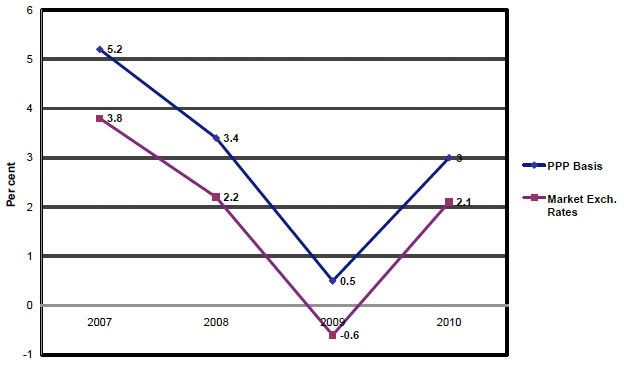

Delegates to the World Economic Forum at Davos this year came despondent and left in despair. Both the discussions and the new evidence released at and during the Forum indicated that the global crisis was not just bad, but worse than originally anticipated. One damaging projection came from the IMF in its January 2009 Update to the World Economic Outlook, which declared: “Global growth in 2009 is expected to fall to ½ percent when measured in terms of purchasing power parity and to turn negative when measured in terms of market exchange rates. This represents a downward revision of about 1¾ percentage point from the November 2008 WEO Update.”

Chart 1: IMF’s Revised Projections of Global Growth, 2009-10 (%)

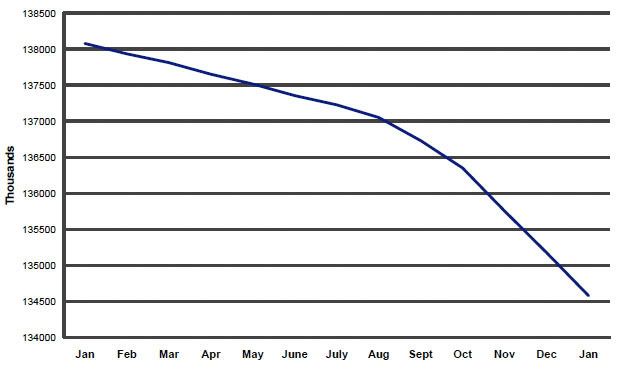

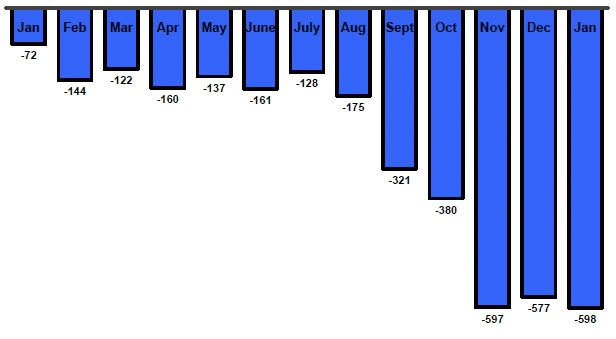

Moreover, data released in recent months by the US Bureau of Labour Statistics points to a sharp fall in non-farm employment in the US in recent months (Chart 2). The monthly decline in nonfarm payroll employment touched 598,000 in January when the unemployment rate rose from 7.2 to 7.6 percent. Nonfarm employment has declined by 3.6 million since the start of the recession in December 2007, and about a half of this decline occurred in the past 3 months (Chart 3). The impact this would have on demand would only aggravate the recession.

Chart 2: Total US Nonfarm Employment, January-December 2008 (‘000)

Chart 3: Absolute Monthly Change in US Nonfarm Employment, January 2008 to January 2009(‘000)

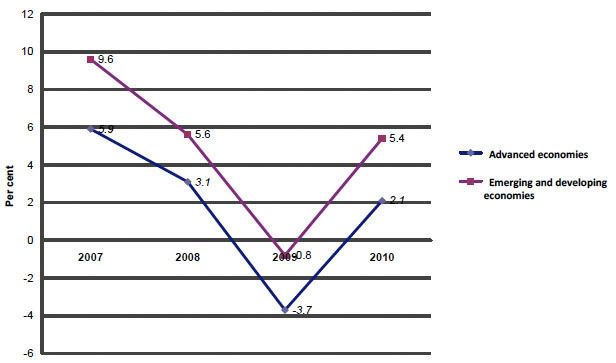

Finally, there is evidence that the global recession led by contraction in the US is transmitting itself through global trade. Export growth from the advanced economies is projected to fall from a positive 5.9 per cent in 2007 and 3.1 per cent in 2008 to a negative 3.7 per cent in 2009. But this trend is not restricted to the developed countries. The relevant figures for the emerging and developing economies are 9.6 per cent, 5.6 per cent and -0.8 per cent (Chart 4). It is small recompense that growth is projected to rebound sharply in 2010. Such projections are suspect, since the IMF has made it a habit of putting out optimistic projections and then revising them downwards.

Chart 4: Actual and Projected World Export Growth (%)

In fact, fear stems not just from the distressing developed country figures. It is also triggered by evidence that the recessionary trend is affecting Asia as well. Developing economies in Asia, which as a group grew at 10.6 per cent and 7.8 per cent in 2007 and 2008, are now expected to grow at just 5.5 per cent or 1.6 percentage points lower than projected as recently as November last year. Japan was already contracting by 0.3 per cent in 2008 and is projected to see that figure falling to -2.6 per cent in 2009. But the three growth engines in Asia — the ASEAN-5, China and India — also now seem to be badly affected by the crisis. The ASEAN-5 economies, which grew at 6.3 and 5.4 per cent in 2007 and 2008, are now projected to grow at 2.7 per cent in 2009 (down 1.5 percentage points from the November 2008 estimates). The corresponding figures for China are 13.0, 9.0 and 6.7 per cent (1.8 percentage points) and for India are 9.3, 7.3 and 5.1 per cent (1.2 percentage points). Moreover, the IMF has predicted a damaging immediate future for South Korea, with its economy projected to contract by 4 per cent this year.

Estimates from national sources and elsewhere are less pessimistic than the IMF, but there is consensus that outside the US it is Asia where the recession is biting most. This is reflected in available estimates on rising employment. According to official Chinese figures, more than 20 million rural migrant workers have lost their jobs and returned to their homes as a result of the global economic crisis. According to these estimates, by January 25, 15.3 per cent of China’s 130 million migrant workers had lost their jobs and left coastal manufacturing centres to return home. And the aggregate figure of migrant job loss does not include those who stayed back in cities in search of new jobs.

India too has made a feeble effort at estimating the impact of the downturn on employment. An official survey by the Labour Bureau focuses on 8 sectors (Mining, Textile & Textile Garments, Metals & Metal Products, Automobile, Gems & Jewellery, Construction, Transport and the IT/BPO industry) to arrive at an estimate of job loss as a result of the economic slowdown in the country. In these sectors it sampled units employing 10 or more workers to make its estimates.

The survey covered 2,581 out of the sampled 3,000 units of which 1,168 were from the Textile & Textile Garments industry, followed by 752 in Metals & Metal Products, 242 in IT/BPO, 132 in Automobiles, 104 in Gems & Jewellery, 103 in Transportation, 19 in Mining, and 61 in Construction. Based on this limited sample, the total estimated employment in all the sectors covered by the survey went down from 16.2 million during September 2008 to 15.7 million during December 2008, implying a job loss of about half a million (Table 1). The actual decline in employment if coverage and method were better is likely to be much higher.

| Period | Average Employment | % Change |

| September 08 | 16.2 | |

| October 08 | 16 | ‐1.21 |

| November 08 | 15.9 | ‐0.74 |

| December 08 | 15.7 | ‐1.12 |

| Average Monthly Change | ‐1.01 |

However, the survey does suggest that employment fell in every month during this period. After September 2008, employment in all industries declined at an average rate of 1.01 per cent per month. A comparison of employment in export and non-export units indicates that employment declined at an average monthly rate of 1.13 per cent in the case of the former, as opposed to 0.81 per cent in the latter (Table 2), pointing to the direct role of the global slowdown.

| Period | Exporting Units | Non‐Exporting Units | Overall |

| October 08 | ‐1.3 | ‐1.05 | ‐1.21 |

| November 08 | ‐0.45 | ‐1.24 | ‐0.74 |

| December 08 | ‐1.66 | ‐0.15 | ‐1.12 |

| Average Monthly Change | ‐1.13 | ‐0.81 | ‐1.01 |

These trends in Asia are of significance because at the time when the crisis was just beginning to unfold, optimists pointed to Asia as the shock absorber that would buffer the global downturn. A decoupled Asia, it was argued, would through its own growth and the demands that it would make on the world’s output ensure that the financial crisis that was largely a phenomenon restricted to the developed countries would not have as damaging an effect on global growth as the pessimists, then in a minority, were predicting.

Implicit in this confidence was the view that Asia was a region where the turn to market friendly policies was undertaken in a form and at a pace that had strengthened these economies and delivered an ”Asian century”. When sceptics pointed to the East Asian financial crisis, they were countered with the view that 1997 was an aberration that resulted from ”cronyism” or some such intangible and not from liberalisation and global integration.

This privileging of Asia was ideologically important since neoliberal policies were fast losing their credibility in Latin America and Africa. Integration and the neo-colonial exploitation of the continent’s resources had not only left much of Africa severely damaged but had undermined the nation state in many countries to a degree where reconstruction required not just radical economic but major political realignments. And in Latin America, with its geographical proximity to the US, the early shift to more liberal, open-door strategies had not just made it the original site of modern day financial and currency crises, but delivered two ”lost decades” when assessed in terms of economic growth.

It needs noting that the fruitlessness of neoliberal strategies forced many Latin American countries, exhausted with seeking foreign capital that triggered a net drain of foreign exchange rather than growth, to search for alternative strategies. In time that enforced search had political repercussions, strengthening democracy and bringing to power in many countries left-of-centre forces voted to power because of their promise to reverse neoliberal policies. The resulting turn in economic policy-making in Latin America has had positive consequences. In the past a crisis in the US and other developed countries proved damaging for Latin American countries dragging them down to degrees far greater than the crisis in the developed countries itself. However, this time around, growth in the developing countries of the Western Hemisphere, which was estimated at 5.7 and 4.6 per cent in 2007 and 2008, is expected to fall to a positive 1.1 per cent in 2009. That is, the continent seems to have escaped the kind of contraction it was prone to in the past, when the global economy faced crises of even lesser intensities.

It was the failure of neoliberalism in the rest of the world that resulted in Asia emerging as its showcase, with global capital talking up these economies and attempting to garner the support of domestic elites for neoliberal policies. As success accompanied each turn in policy, the shift to a regime that opened these economies to trade, foreign direct investment and purely financial flows intensified. Asia came to symbolise the benefits to be derived from liberalisation and global integration and epitomise the view that the world is flat with no walls to climb.

Over the last two decades and more this shift towards neoliberal strategies has indeed transformed Asia’s relationship with the rest of the world. While the region was earlier home to a few mercantilist, export-oriented economies like Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, in time every Asian economy, including the biggest, was looking for a market abroad with some like China proving extremely successful in manufacturing and others like India in services. Moreover, while Asia could be proud of a high degree of regional integration through trade and investment flows, this integration reflected not the decoupling of Asia from the rest of the world but the creation of an export platform in which multi-country production networks created products that were targeted at world markets. Production processes were segmented, each segment located at appropriate sites that generated intermediate products that were combined at the final location (such as China) to be shipped abroad.

The other impact of the process of liberalisation and integration was a sharp increase in foreign investment flows to the region, including large inflows of portfolio capital. A concomitant of this inflow was the liberalisation of rules regarding the presence and operation of foreign firms, including financial firms like banks, merchant banks, insurance companies, hedge funds and private equity firms. Capital inflows in many countries in the region were far in excess of that needed to finance their current account deficits. In fact, some countries with current account surpluses were also recipients of large capital inflows.

If capital inflows were not needed to finance net current foreign exchange expenditures, and the exchange rate regime was liberal, central banks had to intervene in the market for foreign exchange to stabilise appreciating currencies, since such appreciation would subvert the process of export-led growth. A consequence was the accumulation of large foreign exchange reserves in the vaults of the central banks in a number of Asian economies. These reserves, as is now well known, were invested in ”safe” and liquid assets like US Treasury bills and other forms of agency bonds denominated in dollars. That is ”foreign savings” flowing to Asian emerging markets were not needed to finance domestic investment because domestic savings rates were adequate to sustain the relatively high rates of investment in these economies. The idea that there was a ”savings glut” in these countries that accounted for capital outflows from them was a misconception.

This did not mean that foreign exchange inflows were not important for growth. The liquidity overhang these flows generated and the change in financial behaviour that financial liberalization resulted in broadened the market for housing investments, automobile purchases and durable consumption, since even those with relatively insecure jobs were provided access to credit to finance those expenditures. This did expand demand and spur growth. In sum, the macroeconomic scenario in which current account deficits were small or current account surpluses were significant, credit-financed consumption and housing investments were on the increase, investment and growth were high and foreign exchange reserves were large was a result of the ”successful” shift to a neoliberal regime.

Given these forms of integration, it is not surprising that an Asia that was experiencing robust growth till recently has been affected quite adversely by the global financial and economic crisis. As the financial crisis unfolded, foreign financial investors in need of capital to cover losses and meet margin calls at home unwound their positions in Asia, resulting in a collapse in stock markets in many Asian economies. Countries like China, India and Vietnam which had seen their stock markets outperforming their global ”competitors” were also the ones that recorded the steepest falls. The outflow of capital put pressure on many currencies, forcing central banks to unwind a part of their reserves. A liquidity and credit contraction ensued. Foreign financial institutions that were located in these countries and were facing difficulties in global markets had to downsize or close, leading to ripple effects in domestic economies. Domestic financial institutions exposed to sub-prime mortgage-related assets recorded large losses. Finally, the global economic recession slowed export growth in these increasingly export-driven economies. All this generated an Asian version of the global financial and economic crisis, which is what the collapse in aggregate growth figures reflects.

The intensity of this Asian crisis sends out a larger message. Neoliberalism had failed in Africa and Latin America but had earned a lease of life in Asia, where it was not imposed on but owned by many national governments. The first challenge to the regime came in 1997 when the financial crisis broke out in some of the strongest economies in the region. But the forces advocating neoliberal ideology survived that challenge and intensified the process of liberalization and integration. The current crisis poses a second and stronger challenge because finance capital that advocates neoliberalism is seen as responsible for this crisis. It is to be seen whether the advocates of neoliberalism will overcome this challenge as well or whether the ideology would be fundamentally discredited.

C.P. Chandrasekhar is Professor at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning at Jawaharlal Nehru University. He also sits on the executive committee of International Development Economics Associates. Jayati Ghosh is Professor of Economics at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning at Jawaharlal Nehru University. Chandrasekhar and Ghosh co-authored Crisis as Conquest: Learning from East Asia. This article was first published by MacroScan and International Development Economics Associates in February 2009, and it is reproduced here for educational purposes.