Most Iranian politicians, no matter what faction they belong to, place an inordinate amount of faith in the concept of privatization. Whatever woes the Iranian economy may suffer from, privatization seems to be the solution. All four candidates in the June election spoke about the need for privatization of state-owned enterprises, with little difference in policy between their positions. Supreme Leader Khamenei has continually supported the transfer of state assets to the private sector, usually arguing (as he did in March of 2007) that privatization would revitalize the Iranian economy and be the “most effective way” to counter the “economic war” against Iran by Western states.

But in a recent decision by the Privatization Organization (the governmental body that supervises the transfer of state assets) to hand over the International Tehran Exposition Center to the Armed Forces Social Security Organization, a microcosm of the reality of Iran’s privatization process became apparent.

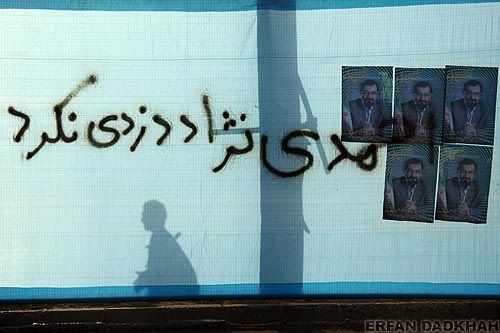

“Ahmadinejad didn’t steal,” spray painted, in part, across campaign posters of the other principlist candidate, Mohsen Rezaei. Photo/Erfan Dadkhah |

After the contested June 2009 election, some commentators in the Western press wrote that the real battle between the factions was over the coming spoils of privatization. For some, Mir Hossain Mousavi’s backer, Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, represented the forces of unbridled Iranian capitalism waiting to swoop up the long autarkic sectors of the Iranian economy: banking, public construction, gas, and perhaps even oil. Through this view, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad became the strange bedfellow of the part of the Western left who saw in Iran’s marketization a forceful hand as evil as it was invisible.

For others just recently acquainted with Iranian politics, the real villain was President Ahmadinejad, whose administration talked “left” but walked “right.” The privatization process did not end under his watch, even as the President railed against the horrors of economic liberalism in his provincial trips. Instead, it was hijacked and made even more opaque, funneled into the President’s “justice shares” program that few experts can claim to understand. Yet Mousavi, whose political origins lie in one lineage of the Iranian left, in his campaign actually promised not to end the “justice shares” program, only improve upon it.

The problem with both of these views is that they significantly overestimate the speed of privatization in Iran and its effects. Before ascribing characteristics such as “neoliberal” — which is sort of a pejorative term for laissez-faire style capitalism — to one or the other political faction, it would behoove oneself to ask an Iranian economist (many of whom were trained in the most prestigious Western economics departments) if the Iranian economy is really on the course of Russian-style privatization and cowboy capitalism. As soon as they were done laughing, they’d ask if you had any advice how to actually get there.

Tehran’s International Expo Center is a huge complex where a variety of conferences and trade shows are held, such as the popular annual spring book fair. The scandal broke in late July when, partly based on reports by economic journalists working for the newspaper Etemaad-e Melli, it became apparent that 95% of the Expo Center’s lands and assets were being transferred to the Armed Forces Social Security Organization (AFSSO) without any process of bidding by other possible buyers. Instead of an auction, the Privatization Organization quietly agreed to a contact giving ownership of the Center in exchange for the cancellation of debt owed by the government to the AFSSO.

The Chamber of Commerce, the Council of Cooperatives, and even the Ministry of Commerce (who is supposed to authorize the privatization of any state asset) claimed the transfer was illegal and called for its halt. According to Hossein Rahmaninia, director of the Chamber of Commerce, the Expo Center had been promised to the non-governmental sector, and the illegal transfer was a “great oppression of Iran’s commerce.” After all, if 95% of the Expo’s assets were to be transferred to a para-governmental body, which the AFSSO certainly reasons itself, then this was not privatization at all. Since the Expo never went on the auction block, its total value is still unknown but is estimated in the hundreds of millions of dollars. With protests coming from the private sector, the Majles, and even within the administration, it now seems likely the transfer will be canceled and a bidding process re-scheduled. The AFSSO has said it will take part in the new auction to purchase up to 51% of the available shares.

There are two scandals here, not one.

The first scandal is the revelation that a main buyer of government assets over the last decade has been the para-governmental sector, which includes state banks, government-linked investment and holding companies, religious foundations, and pension funds. For those who follow Iran’s economy, though, this is not really news. In 2007, for example, 20% of the National Iranian Copper Industries Company was “privatized” for the price of $1.1 billion USD. The buyers? Mostly other state-owned companies, including the pension funds of the steel and state broadcasting industry!

There is a benign reason that explains this outcome, if one chooses to believe it. Social Security Organizations have existed in Iran’s main governmental agencies since before the Revolution, to provide health and pension insurance for its ever-growing public sector workforce. Like other public sector pension funds around the world, including those in wealthy countries, they amass pools of capital through individual and government contributions but need to keep the pool growing in order to provide for their retirees. If you ever see an Iranian on a pension from the National Iranian Oil Company, you’ll realize it’s not too shabby a retirement plan. Of course, Iranian pension funds do not have much ability to invest their capital outside the country, due to the “economic war” — US-led financial sanctions — the Supreme Leader often likes to bring up. So, their only option is to invest in Iran’s economy, and hope their capital grows in tandem with the rise in pension and health costs for their employees. The business press in Iran is littered with one-paragraph news items that announce the purchasing of privatized shares by pension funds, if one bothers to look.

However, why would the government be in debt to a pension fund? Well, according to the Constitution, the government is responsible for the national welfare system. Like pension funds every where in the world (before the 401k), the Iran government is liable to pay into them a certain amount each year. Except that Iran’s government at times has failed to pay part of its liabilities (this is what it means when pension funds become “underfunded,” as often occurs in the US). In 2000, during the Khatami administration, the newspaper Hamshahri reported that the government owed $1.2 billion USD to two of the main Iranian Social Security Organizations. Since then, due to increases in oil revenues, Iran has been able to lessen its debts to quasi-governmental pension funds, but it is not surprising to see a debt to the AFSSO announced in the press.

So, the domestic scandal is that instead of fostering transparency and supporting the Iranian private sector, an agency of the government is circulating valuable assets to a sort of “near cousin” in a deal that, while opaque, is quite common. It is not the picture perfect market-friendly environment a foreign investor likes to see, but it is certainly business as usual for middle-income countries most anywhere in the world. What’s the other scandal?

The other scandal is that you’ve probably never heard of any of this before, even if you belong to the astute readership of Tehran Bureau. That it has been two months since the most historic election and series of post-election events in post-revolutionary Iran, with the entire world watching, and who knows how many millions spent on “the story,” and yet few have looked into the basic reality of Iranian state-business relations. In other words, as the sides attacked each other regarding who was benefiting from privatization, the Western press fell for the rhetoric of Iranian factional politics. Certainly not the first time, of course. But this rhetoric turned into fodder for battles outside of Iran over the meaning of the Iranian election. Scandalous, no?

Mohammad Khiabani is a writer in Tehran, Iran. This article was first published by Tehran Bureau on 17 August 2009; it is reproduced here for fair-use educational purposes.