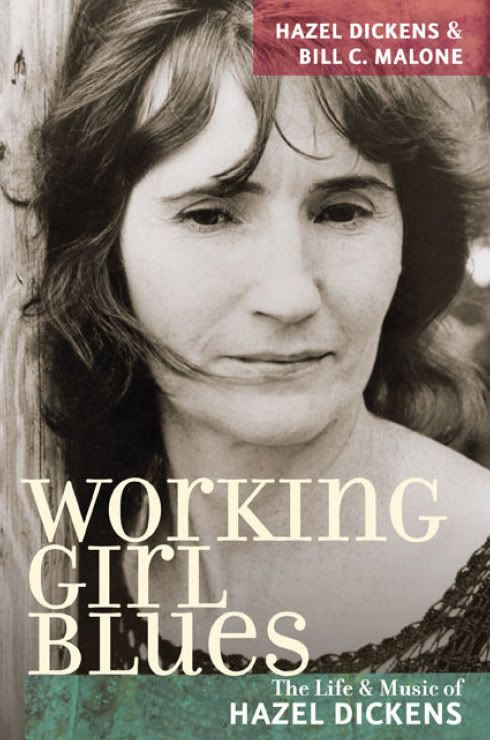

Hazel Dickens, Bill C. Malone. Working Girl Blues: The Life and Music of Hazel Dickens. Music in American Life Series. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008. Illustrations. ix + 102 pp. $60.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-252-03304-9; $17.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-252-07549-0.

Working Girl Blues encompasses three main sections: “Hazel Dickens: A Brief Biography,” twenty-nine pages long, by Malone; “Songs and Memories,” which includes the texts of forty of Dickens’s compositions, along with a commentary on each by Dickens; and “A Hazel Dickens Discography.” Additionally, forty-one visual illustrations (most of them photographs) document various phases in Dickens’s personal and professional histories.

The book exhibits the excellent historical scholarship characteristic of Malone, and Dickens’s contextual framing of her compositions is valuable on multiple levels. Occasionally, Working Girl Blues drifts in the direction of uncritical celebration, thus arguably doing something of a disservice to the musical traditions that Dickens represents and to other artists who represent them as ably but have not been accorded the iconic status ascribed to her. However, the tendency to praise Dickens’s work without analyzing it as rigorously as one might that of other musicians is hardly unique to this book; it seems to be typical of most literature on Dickens. Thus, it really is an issue unto itself that need not distract us here.

Malone’s “A Brief Biography” is a highly effective portrait of an artist who has practiced her art in the interest of social justice. As usual, his prose is impeccable in its pacing and strikes an ideal balance between mellifluousness and clarity, between descriptiveness and directness. His telling of Dickens’s story conveys a sense of drama but never resorts to histrionics and only rarely to hyperbole. His original research, including conversations with Dickens, enables him to enliven the narrative with firsthand anecdotes and to integrate the details of her life more fully than might otherwise be possible.

Though Malone seldom interrupts the narrative to interpolate theoretical or interpretive content per se, he does construct it in such a way as to accentuate significant themes. Perhaps the most pervasive of these is the impact of Dickens’s experience as a native of Appalachia living in the Baltimore-Washington area on her social frame of reference and, consequently, on her artistic development. Malone indicates (without saying so explicitly) that as someone whose understanding of rural Upland southern culture informs her understanding of urban American culture and vice versa, Dickens — like many artists of similar backgrounds — occupies a “third space” (to borrow a term from Homi Bhabha), in which she is able to reflect critically on both and to express her reflections in art. Thus, “A Brief Biography” contributes substantially to the growing scholarly literature on expressive culture of people who migrated from the rural Upland South to urban, industrial centers in adjacent regions for economic reasons during the mid-twentieth century.

Malone’s point of entry into the narrative of Dickens’s life is his vivid description of her voice — “stark, keening, and persuasive” — as heard in “Black Lung,” an original composition inspired by the death of her own brother and included in the soundtrack of Harlan County USA (p. 1). She had been a professional musician for at least twenty years and a recording artist for more than ten by the time the film appeared in 1976, but it was that documentary, as Malone notes, that first gave her music wide exposure.

Dickens was born in Mercer County in southern West Virginia’s coal country in 1935. Malone discusses her family, which, according to its own oral history, is related to Charles Dickens — appropriate, albeit undocumented. He also discusses her early religious formation, which was situated in the Primitive Baptist Church. Primitive Baptists are distinct from most other Baptist bodies (and certainly from most Evangelical Protestant denominations) in aspects of doctrine and practice, and although Dickens’s views on religion throughout her adulthood have been ambivalent, the defining characteristics of the specific religious milieu in which she was raised and her responses to them — both positive and negative — indelibly influenced her worldview and identity.

So did music — whether aurally transmitted vernacular music of central Appalachia or radio-transmitted performances by Roy Acuff, Bill Monroe, Ernest Tubb, and especially the Carter Family. “Hazel clearly loved a broad range of country music, from the very traditional to the honky-tonk melodies of Texas. . . . At that time, country music was not yet rigidly subdivided into subgenres,” Malone rightly observes (pp. 5 and 8). All of these influences contributed to the Dickens family’s tradition of music making.

Hazel and other members of the Dickens family carried that tradition with them when they, like many natives of southern West Virginia who recognized that prospects for economic self-betterment there were diminishing, moved to Baltimore in the 1950s. However, Hazel’s development as a musician was far from complete when she arrived there. On the contrary, as Malone suggests, her new milieu would prove at least as consequential an influence on her artistic formation as her original one. He writes, “Baltimore was in the throes of a musical revolution in the late fifties. On the cusp of the folk revival, the city served as an incubator of the emerging bluegrass phenomenon” (p. 10). Within that lively environment, Dickens honed her skills as a performer and also became acutely aware of the sexism of male honky-tonk patrons and musicians, many of them fellow Appalachian migrants, motivating her to write songs from a feminist perspective years later.

An important trend in Dickens’s life — one that constitutes a leitmotiv in Malone’s biography — began soon after she arrived in the city. Over the next two decades, she met a succession of politically progressive urban natives from comparatively elite social and educational backgrounds. They appreciated her rich cultural background, recognized her talent and inner strength, and provided personal and professional support. Dickens, in turn, admired and adopted many of their moral convictions and looked to them as mentors as she navigated the unfamiliar waters of city life and the musical profession.

First and foremost was Mike Seeger; as a conscientious objector during the Korean War, he worked at a sanatorium where Dickens’s brother was a patient. He began playing music with the Dickens family and encouraged their involvement in the Baltimore-area music scene. Another was Alice Gerrard, who had entered the world of old-time and bluegrass music via the folk revival and was living in Washington DC. Dickens formed a musical partnership with her that eventually yielded two albums on Folkways. In the years between the release of the first in 1965 and that of the second in 1973, Dickens and Gerrard “found that an almost cultlike following was developing around their music. Their passionate, spine-tingling harmonies and interesting repertory of songs attracted tradition-minded bluegrass fans,” Malone observes (p. 14). Simultaneously, they garnered enthusiasm among “folkniks” and socially conscious young people.

The evolution of Dickens’s stature as a musical advocate for socioeconomic justice is another thread running through Malone’s biography. In 1967, she and Gerrard joined the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project, in which white and black folk musicians performed before integrated audiences throughout the South. Upon moving to Washington in 1969 following a brief marriage, she vigorously pursued her interest in songwriting, leading to participation in the Smithsonian Folklife Festival at the invitation of Ralph Rinzler, who “was deeply impressed with Hazel because she combined the style and sensibility of a mountain singer with a passion for social justice” (p. 16). Her performance of “Black Lung” at a meeting in Kentucky in 1970 was televised nationally. In 1972, she participated in workshops at the Highlander Folk Center in Tennessee, meeting veteran labor singer-songwriters Florence Reece and Sarah Ogan Gunning. With them, she contributed to an album of mining songs on Rounder Records, with which she had already begun what would prove to be a long, multifaceted association. She and Gerrard released two albums on Rounder, one in 1973 and the other in 1976, before Gerrard opted to pursue other musical goals. These received more exposure than the Folkways recordings, establishing them as pioneers among women in bluegrass.

Malone writes, “Hazel was deeply disappointed with Alice’s departure, but she already had a separate career and identity” (p. 20). The strength of that identity was confirmed the same year by Dickens’s critically acclaimed contributions to Harlan County USA. In the late seventies, after a stress-induced illness, Dickens “vowed to make music on her own terms and conditions and to accept only those jobs that she really wanted to play,” collaborating selectively with longtime friends and with leading figures in bluegrass (p. 21). During the 1980s, Dickens recorded three solo albums: Hard-Hitting Songs for Hard Hit People, By the Sweat of My Brow, and It’s Hard to Tell the Singer from the Song. She has since contributed to several other albums and film soundtracks and is herself the subject of an Appalshop documentary film, It’s Hard to Tell the Singer from the Song, produced by Mimi Pickering in 2002.

The many honors bestowed on Dickens by fellow artists and cultural specialists in recent decades, of which Pickering’s film is only one, form a central topic of the latter phases of Malone’s narrative. The 1996 Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife featured a symposium/concert entitled “Hazel Dickens: A Life’s Work,” in which some of the most accomplished American folk musicians participated. She received a National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellowship in 2001. Malone emphasizes that Dickens especially appreciates the admiration expressed by younger musical colleagues.

Nonetheless, Malone writes, “Hazel’s commitment to social justice has not been dampened by her successes, nor has her conviction that music should be put to the service of working people’s welfare,” noting that she continues to perform at events in support of labor (p. 24). He concludes, “In the sanctuary of her apartment in Washington, D.C., a mountain woman named Hazel Dickens is still writing songs that challenge the easy complacency and corporate arrogance of our time” (p. 27).

The degree to which Dickens’s critical reflections on her personal experiences have influenced her artistry becomes even clearer in the next section of Working Girl Blues, “Songs and Memories.” One of the forty songs discussed, “It’s Hard to Tell the Singer from the Song” — namesake of one of her solo albums and of Pickering’s film — describes “a hurtin’ woman who lives the songs she sings,” who, as Dickens says in her commentary, “experiences a lot in life, but loses some of herself along the way.” Dickens remarks, “When I wrote this song, in 1986, I was probably writing my autobiography and didn’t know it” (p. 52).

The quasi-autobiographical nature of “It’s Hard to Tell the Singer from the Song” is far from atypical; Dickens draws on specific real-life experiences in many of the compositions featured here. Three of them directly express the emotions of a rural Upland southern migrant to the city who confronts the challenges of navigating between the two worlds and misses the familiarity of home, bringing Bhabha’s observations to mind once again. Two of those — “Mama’s Hand” and “West Virginia, My Home” — are among Dickens’s best-known songs.

Her commentary on “Hills of Home,” however, is perhaps the most interesting from a historical perspective. It might surprise readers who hold the common misconception that the southern West Virginia coalfields remained sparsely populated and essentially premodern until recently, unaware that the region actually experienced population growth and modernization with the early twentieth-century expansion of mining, followed by declines in population and economic opportunity in mid-century because of mechanization. Dickens writes, “Small coal camps became ghost towns compared to their heyday. When I was younger, I could take the train or bus right to my hometown. Now when I take the train, I have to get off twenty-nine miles from my destination, and it only runs three days a week” (p. 64). As the song says, “Gone are the echoes of old familiar sounds” from the hills, which have “seen a lot of leaving in their time” (p. 64).

Several selections reflect another facet of Dickens’s experience of rural Upland southern life: her upbringing in the distinctive Primitive Baptist milieu. In her commentary on “Won’t You Come and Sing for Me,” the first entirely original composition that she recorded, Dickens writes, “When I was growing up, I was impressed by the love and kindness that was openly shared and displayed among the brothers and sisters of the old Primitive Baptist church. . . . This kind of humility and harmonious spirit of a common people inspired me to write this song as a tribute to that place and time tucked away in the corner of my memory” (pp. 45-46).

Of course, Dickens’s solidarity with “common people” manifests itself in many of her best-known compositions, some of which recall specific historical events. “The Yablonski Murder,” for example, commemorates the killing of Jock Yablonski, a candidate for president of the United Mine Workers of America, by assassins hired by the corrupt incumbent. “Mannington Mining Disaster” decries corporate negligence that contributed to a deadly mine explosion in northern West Virginia in 1968, as well as a culture that discouraged mining families from considering vocational options other than mining for their children: “Be like daddy bring home a big pay” (p. 71).

Among the many other compositions addressing social issues are “Will Jesus Wash the Bloodstains from Your Hands?” prompted by the suicide of Dickens’s nephew, a victim of the effects of mental trauma suffered in war, and “Working Girl Blues,” reflecting Dickens’s experience of working in an unrewarding job while struggling to meet other personal and professional obligations. Another expression of challenges faced by working families is “Lost Patterns,” which Dickens justifiably describes as “possibly some of my best writing” (p. 42). Patterns in the linoleum flooring of a house that have faded away from years of wear serve as a metaphor for the lost affinity between the home’s occupants, whose marriage has failed under the tedium of working to make ends meet. As the husband drank alone in the kitchen, “Every now and then his empty can would shatter the silence of the room / As it landed on her pretty face / Still smiling from the broken picture frame” (p. 42).

“Lost Patterns” is one of several songs discussing aspects of relationships that have ended, are ending, or are not as fulfilling as they ought to be. Some, such as the autobiographical “My Better Years,” eloquently express the complicated mixed feelings, both positive and negative, that one might have toward a former companion. Others criticize men who fail to appreciate women as multidimensional people rather than merely as sources of companionship. Among these is “Old Calloused Hands,” written in honor of one of Dickens’s sisters, “one of the best and most loving persons I’ve ever known,” who, for the sake of her children, chose to remain married to a man who mistreated her (p. 54).

Perhaps Dickens’s best-known feminist song is “Don’t Put Her Down, You Helped Put Her There.” It recounts the loss of self-worth experienced by women whom Dickens encountered early in her career, and who were subjected to crass attitudes and exploitative treatment by male musicians and club patrons. “They were mostly country boys who had moved to the city to find work, but they still had the same old attitudes they had grown up with,” she explains (pp. 50-51). The song seems as though it might have been written to say “Yes, I’m afraid you’re right” to the singer of “The Image of Me” (the Wayne Kemp composition recorded by Conway Twitty, Charley Pride, and others). Dickens notes, however, that many male bluegrass and country musicians today “tend to be more open and sensitive in their working relationships with women” (p. 50). Furthermore, “Songs and Memories” includes what Dickens describes as “the first positive love song I’ve ever written,” “My Heart’s Own Love,” composed in 2002 (p. 80).

Finally, several songs integrate multiple themes already mentioned. “Pretty Bird,” an a cappella composition, incorporates imagery and phraseology characteristic of Anglo-American balladry. The singer urges a pretty bird — a metaphor for a young woman — to “fly away” from what seems to be a promising new companionship, “for he’d only clip your wings.” “Pretty Bird” speaks of an emotional need to transcend limitations — both those of a circumscribed cultural milieu and those of inequitable relationships. “Coming from such an isolated area and a different culture, I felt like I was always trying to play catch-up in my life and workplace,” Dickens comments. “I envied the little bird sitting on the high wire. It could fly away at any given moment and be free” (p. 57).

“A Hazel Dickens Discography” doubtlessly will be useful to many readers of Working Girl Blues. It does not list any recording (completed or in progress) that fits the description of “the new project with Rounder in 2004” that Dickens mentions in “Songs and Memories,” leaving the question of what that project might be unanswered (p. 58). Also, it states that “a tribute album of Hazel Dickens songs” featuring luminaries in American roots music “is forthcoming from Rounder Records in 2007” (p. 87). My online research did not indicate that any such recording has yet materialized, but perhaps the project is still under way. Generally, this discography is laudably thorough and easily comprehensible.

Working Girl Blues succinctly yet comprehensively surveys a remarkable artistic career and the circumstances in which it has progressed from the perspectives of the artist herself and a distinguished scholar who is, in significant respects, a kindred spirit. Despite its occasional lapses in interpretive rigor, this book will be an invaluable resource to anyone who wishes to understand the contexts surrounding Dickens’s achievements and the historical developments of which her life is illustrative. It will be a source of immeasurable inspiration to anyone who aspires to give artistic expression to the struggles, frustrations, virtues, and hopes of working people in future times, as Dickens has done so ably in our own.

Matthew Meacham, Folklore Program, Department of American Studies, University of North Carolina. This review was published by H-Southern-Music (May 2009) under a Creative Commons license.