How Should Venezuela Face the Coming Recession?

Presently much of the industrialized world is in a severe economic recession. The United States, Europe, and Japan are definitely in one and other important countries such as China are close to being in one.

So far most South American countries have not entered into a recession. The primary reason for that is that most of them export commodities — Venezuela and Ecuador oil, Chile copper, Argentina and Brazil food — and commodity prices were actually booming until quite recently. That is, whereas what put the U.S. economy into a recession was the collapse of the housing bubble, which occurred in 2007 and pushed the U.S. into recession at the beginning of 2008, South American countries didn’t see commodity prices decline until this past fall. Hence the recessionary pressures are only just now beginning for most Latin American countries. But, while the recession may be late coming to South America, rest assured it is coming.

The question then becomes what should be done about it? Should countries hunker down by cutting spending in an attempt to keep their budgets balanced and not deplete their foreign reserves? Or should they follow an expansionary policy, ie increase government spending in an attempt to keep their economies growing?

One economist, Mark Weisbrot, has given his views on this in an article entitled “South America: Recession Can Be Avoided.”

In this article Dr. Weisbrot argues that South America is well positioned to ride out the recession first because it isn’t as tied to countries like the United States as it used to be, second because it didn’t get caught up in the U.S. financial shenanigans, and third because it has socked away a lot of savings that it can now draw on. But in terms of what exact policies they should follow in the face of a potential recession Dr. Weisbrot says the following:

So there is no reason to expect South America to face the kinds of economic troubles that currently plague the United States. However, South America is still linked to the world economy through trade and investment, and will be affected by the world slowdown. It will therefore need to pursue expansionary monetary and especially fiscal policies — just as the rich countries are doing – in order to maintain healthy economic growth.

China did this during the Asian economic crisis ten years ago, and maintained solid growth while its neighbors — Indonesia, South Korea, Thailand and others — suffered serious losses of output and employment and watched tens of millions sink into poverty. The Chinese temporarily changed their economic strategy and invested hundreds of billions of dollars in public works and infrastructure. They are responding similarly to the current crisis, deciding this week to increase spending on infrastructure, transportation, and social welfare programs over the next two years by $587 billion. (emphasis mine)

Dr. Weisbrot then goes on to explain some of the constraints to following such a policy that South American governments may face and how they can overcome them. However, those details are unimportant to me as I disagree with his initial premise — that South America should pursue an expansionary fiscal policy just like rich countries are doing. The rest of this post will be dedicated to explaining why I don’t think they (or better stated Venezuela) should pursue such a policy, what alternative policy I think they should pursue, and how we will be able to tell if their policies are effective.

There is one additional point of clarification. In this post I will only deal with Venezuela in part because this blog focuses on Venezuela and in part because I don’t know enough about other South American economies to comment intelligently on them.

In order to see why I don’t think Venezuela should resort to expansionary fiscal polices (or Keynesian or counter-cyclical policies as they are sometimes called) I first have to tackle something more basic — what Venezuela’s economic situation is in general and what should be done to promote its long-term development.

Venezuela of course is underdeveloped, and, while certainly it isn’t among the poorest of countries, it is poor relative to the U.S., Europe, Japan, and other developed countries. To get to what most people would consider an adequate level of economic development it will have to have rapid growth for several decades. Therefore, in judging what policies should be followed now, it is as important to consider how they affect Venezuela’s long-term growth prospects as what they would do this year or next (or the former is even more important than the latter). That is, in my view there are more important issues facing Venezuelan policy makers than whether Venezuela goes into a recession right now, namely laying the foundations for longer-term sustained growth. Given that Venezuela is in effect in a permanent state of depression, its focus has to be getting out of THAT depression, not worrying about a recession this or next year.

How should Venezuela achieve long-term growth? Interestingly, I’ve never seen Dr. Weisbrot write an article laying out what Venezuela should be doing to promote its long-term development. But, because different conceptions of how that development will take place are probably responsible for our differences, let me at least summarize my general ideas on how that development would take place:

First, Venezuela would need very high levels of investment both in physical plant and equipment and education. For normal growth most economies need 25% of GDP to be invested. But third world countries that have industrialized generally have investment rates of between 40% and 50% of GDP. Thus, for Venezuela to have sustained rapid growth, it will need to promote investment over consumption in order to ensure high rates of investment needed to provide that growth.

Second, it is unlikely that this investment will come from the private sector. This is for several reasons. Private capital prefers investments where it can get quicker and safer returns such as real estate and commerce. Also, particularly in a country like Venezuela, there just aren’t that many private people or organizations with the large pools of capital needed for long-term industrial projects (ie, you don’t start up an auto industry or even an home appliance industry with chump change). Finally a very large portion of private capital flees to places like the United States that are considered safer places to invest.

This leads to a very key point — that Venezuela needs lots of investment and it is the Venezuelan government that will need to do the investing. Plain and simple, no one else will do it.

Note, also, that, although a large debate has raged on this blog over whether to use exporting or import substitution to promote development, for purposes of this discussion it doesn’t matter which you use, all of the above still holds. Namely, you need high rates of investment and it is the government that will have to do the investing.

What does all this have to do with how Venezuela should deal with a potential recession? Well, it should be fairly obvious.

Because it is government investment in industry, agriculture, and education that will lead the way to long-term development the government has to be VERY careful about how it spends its money. To the extent it spends its money on the aforementioned investments it can potentially grow faster over time whereas to the extent it spends its money supporting consumption (which ranges from social program expenditures, to paying the government payroll, to giving out CADIVI dollars for travel and the importation of consumer goods) it will be sacrificing investment and hence future growth.

Getting down to the nitty gritty this means the following: Venezuela presently has lots of money saved up. A large part of that money is in something called the National Development Fund or FONDEN. Another large portion is in its foreign reserves held by the Central Bank. In line with what I have said above, Venezuela should spend those dollars on development projects — building factories, importing machinery, constructing irrigation systems, creating needed infrastructure, etc. WHAT IT SHOULD AVOID USING THOSE FUNDS FOR is to cover for declining oil revenue by using them to meet the government’s payroll, or by giving the money to CADIVI to cover the costs of imported consumer goods and the like.

Of course, it may be unavoidable that some monies be used to make up for budget shortfalls and fund current consumption. For example basic social programs need to be maintained and people need to be kept out of poverty. Critical imports such as food and medicines may need to be funded out of savings as well. But given that using the tens of billions of dollars that Venezuela has saved to pay for those types of things represents sacrificing the future to pay for the present it is critical that they be kept to a minimum. In sum therefore we see that the Venezuelan government should NOT be doing what the rich countries are doing — trying to pump as much money into the economy in any and every way possible — but rather should seek to reduce waste, cut back on unnecessary expenditures, and to the absolute greatest extent possible maintain all investment projects.

Viewed from this perspective the government’s move to restrict dollars given out for travel is exactly right and indeed a very good sign that the government is taking at least some of the appropriate measures.

Now the obvious question is why if Dr. Wiesbrot is a very capable economist who is well versed in the Venezuelan economy is he seemingly recommending the exact opposite?? This is a good question indeed. If we were really lucky maybe he would show up and tell us.

Barring that I can only guess at the following, and that is that he seems to attribute, almost, the status of a developed country to Venezuela. That is, the United States government doesn’t need to conserve money for investment because the government isn’t who does most of the investing — private individuals and companies do. Further, the U.S. is already developed so it doesn’t need high rates of investment. With moderate rates of investment and moderate rates of growth the U.S. can maintain its standard of living. So the government can and does simply concentrate on providing services and social programs and maintaining macro-economic stability by spending when needed. Of course, the U.S.’s profligacy may well catch up with it and begin to sink its economic status, but the point is the U.S. government doesn’t have to actually devote large sums of its money to investments in industry and agriculture the way Venezuela does.

Of course, I am sure Dr. Weisbrot on an intellectual level understands that distinction. But given his lack of an articulated development program he at least SEEMS to just fall back on aping the economic strategy of the developed countries — pumping money into the economy to keep it growing. That may work in the developed world where once a economic recovery gets legs private industry will start making significant investments but it will never work in Venezuela where private industry barely exists and will certainly never make the investments necessary for Venezuela to develop.

A question naturally arises from my assertion that Venezuela should not use its savings just to maintain current growth, and that is what will happen to Venezuela if it goes into a recession now and what good is investing in industry and agriculture if practically the whole world is in a recession (ie where will they sell their goods)?

The first answer is that without either an immediate and sharp rebound in oil prices or massive spending from accumulated savings Venezuela will almost certainly go into a recession, most likely in the second half of this year. Right now they can’t even fund their current budget yet even that budget represents a significant reduction over the total amount they spent in 2008. I doubt oil prices will rebound much if at all this year, so, barring Chavez being willing to spend out of savings at the rate of $2 billion per month, the country will go into a recession.

Of course, this will create hardship. Some people will lose their jobs. Some people who keep their jobs will see their purchasing power decline. There will be less consumption and that will be felt.

Yet none of that is disastrous. Even with a drop in employment and consumption Venezuelans would still be better off than they were even a few years ago. Further, if the government maintains key social programs like Mercal, Barrio Adentro, and some of the other Missions, they can keep poverty rates from going up and ensure that people’s basic needs are met while still conserving most of their money for investment.

The second answer is that making new large-scale investments even in the midst of a recession still makes sense and in fact is necessary. First, it needs to be noted the recession is not likely to last forever — the whole world’s economy is not going to permanently collapse (well, so I hope). Second, investments take time to come to fruition. For example, any new factories being constructed now most likely won’t begin producing for a couple of years, and by that time the world economy should be improving.

Further, Venezuela can also follow an import substitution policy — that is attempting to produce some of the things it currently produces. Venezuela currently imports about $45 billion worth of goods per year and beginning to produce locally even a portion of those goods would give its industry and agriculture significant room for growth. This holds true even if imports are declining and consumption as a whole is declining in Venezuela because as long as Venezuela starts to produce what it formerly imported it can grow.

To show how this works, let’s take an example of widgets with Venezuela consuming 100,000 widgets annually and importing all of them. Say it builds a factory a to produce 50,000 widgets per year. That factory will be productively employed and will represent growth when it goes on line and starts making those 50,000 widgets and there will be a market for those widgets even if overall widget consumption drops to 70,000 per year due to the recession because it will simply displace imports which would have still been 70,000 if no factory had been built. Following this example you can see a country can still grow its domestic industry quickly with import substitution policies even in the face of a recession.

I will now summarize my conclusions in two parts — one laying out what specific policies I believe Venezuela should follow right now and then I will outline how we can tell if those policies are working or not working.

The policies I believe Venezuela should follow are:

- Reduce all non-essential expenditures. By this I mean cut back on CADIVI outlays of money, trim the bloated government payroll, cut wasteful subsidies (such as subsidizing middle-class housing purchases), limit salary increases and bonuses for government workers, and stop buying fancy military equipment (these are just examples, there are many other things that could be cut).

- Re-instate or increase taxes that were cut during the oil boom — specifically the IVA and financial transactions tax.

- Either devalue completely or at the very least create a dual exchange rate to stop wasting money on subsidized travel and fancy consumer goods.

- Ensure that critical safety-net social missions remain fully funded and possibly even increase funding for them as during a recession more people may need their services.

- Above all DO NOT CUT BACK ON ANY INDUSTRIAL OR AGRICULTURAL PROJECTS. Those must continue to go forward and in fact if possible the amount of resources put to this use should be increased.

- Expenditures on education, which is a form of investment and a critical component of any serious development program, should be increased but better focused on critical needs (ie, more for engineering, less for “social communications,” whatever that is).

I believe that by following the above polices Venezuela will enter a moderately severe recession which will inflict pain but that it can stay on track with a real development program that can increase standards of livings in 5 or 10 years in a noticeable and sustained way.

Finally, how can we as observers of Venezuela tell if their development program is working even through a recession?

This is relatively simple if we follow the correct statistics. The statistics that need to be monitored are the performance of manufacturing and agricultural GDP relative to overall GDP or non-oil GDP. By measuring the relative performance of those statistics we can determine if the country is truly developing.

For instance up until now overall GDP and non-oil GDP have both grown much faster than manufacturing and agricultural GDP. For example, in the year that just ended total GDP growth was 4.6%. Yet manufacturing growth was only 1.6% and agricultural growth was 2.3%. That is, clearly something besides manufacturing growth was propelling the Venezuelan economy and in fact we know what that was — oil-financed government spending. That manufacturing output grew slower than the overall economy shows that it was not invested in enough to help drive the economy forward but rather was tagging along after the rest of the economy. This means that either there is not enough investment or the new investments haven’t started to come on line yet in significant numbers.

But, going forward, if manufacturing and agricultural GDP grow faster, or in the worst case, shrink slower, than overall GDP or non-oil GDP, this means that Venezuela is still developing even during a recession. Referring back to the widget example we see that in fact manufacturing and agriculture can easily outperform the rest of the economy (in that example using widgets as a proxy for the overall economy we saw that while overall economic activity shrank local production or manufacturing GDP could still increase by having local production substitute imports). The increase in manufacturing and agriculture will represent true and sustainable growth, and while its benefits may not be much noted during a recession, it most definitely will allow for higher standards of living over time.

Knowing this, it will be easy to evaluate Venezuela’s success in 2009. If the overall economy grows 1% but manufacturing grows 5% that means their development program is working — the recession is slowing the overall economy but due to heavy investment manufacturing is growing faster. On the other hand if the economy shrinks say 3% but manufacturing GDP shrinks 8% or if the economy grows 2% but manufacturing only 1%, then it can be said their development program is NOT working because manufacturing is underperforming the economy as a whole.

Of course, being passive observers with no ability to influence Venezuelan policy, all we can do is note whether their policies seem to be working or not working, but we clearly do have a way of telling that. Let’s hope that even through the few difficult years to come Venezuelan policy makers opt to do what will most help the country over the next 10 to 20 years, not the next 10 to 20 months.

Socialism to the Rescue. . .

. . . well maybe not.

Below, from the Economic Statistical Annex to the 2008 Venezuelan Presidential report, we see this:

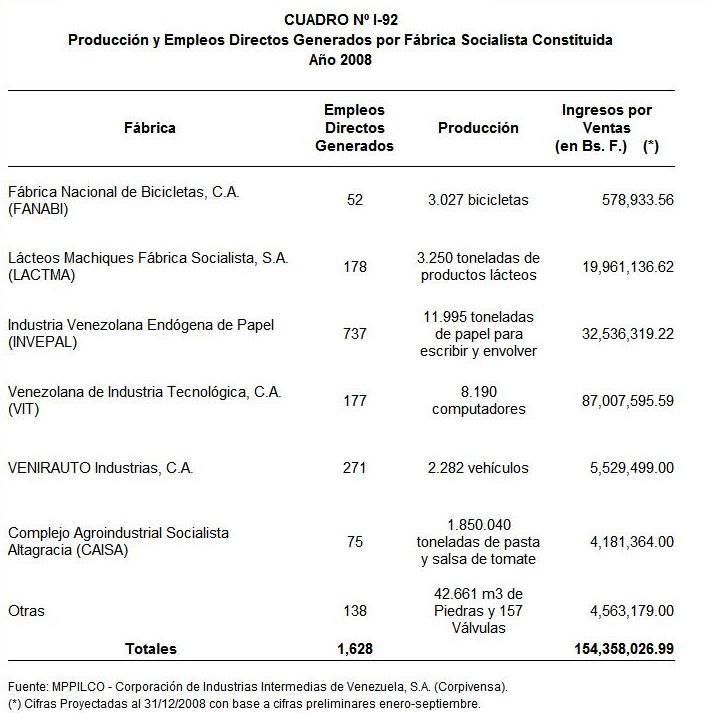

The above spreadsheet shows the 2008 results for all the “socialist” factories in Venezuela. It gives the number of people employed, what they produced and the number of units produced, and the value of total sales.

Note there are three “socialist” factories listed here that everyone should have heard of: the bicycle factory which actually had Chavez show up to inaugurate it and the Venirauto car factory and the computer factory that has been running for a while.

The bicycle factor made a total of 3,027 bicycles. At this rate in 8,000 years they can make a bicycle for all of Venezueala’s 28 million citizens. Of course, in 8,000 years there will probably be a lot more than 28 million Venezuelans. I wonder if they’ve considered the fact that new Venezuelans seem to be made much faster than new bicycles. But at least this factory gave gainful employment to 52 Venezuelans.

Then we have the car “factory.” To the best of my knowledge the most this factory does is assemble some cars from Iranian-supplied parts. Further, having seen it from driving by on the highway, this factory looks quite small. Seeing it I wondered how they could possibly even assemble cars there. Now I know — they make damn few of them. 2,282 last year to be precise.

At least we can’t claim the factory is feather-bedded — it only has 271 employees. The other curious thing is it only had about 5 million bolivares in sales or about $2.5 million dollars. Either it is selling cars for $1,000 a pop or it is giving most of its production away for free.

Finally, we get to the computer factory. This was really a computer assembly plant set up by the Chinese, much like the recently inaugurated cell phone “factory.” It had maybe the best results making over 8,000 computers (I’ll leave it to the reader to calculate how many centuries the average Venezuelan will have to wait to get one of them) with 177 employees.

Oh, and if you have to ask, you can’t afford it. Divide the sales by the units produced and you get about $4,800 per computer. Looks like I’ll just have to stick with my crappy Dell.

So, stripping away all the fancy lighting, makeup, hoopla, and bravado surrounding these factories when they are inaugurated by Chavez on “Alo Presidente,” let’s see what we have in sum total:

In sum total all the “socialist” factories have a total of 1,168 employees and sales of around $75 million dollars. Splitting that output among Venezuela’s 28 million citizens yields something less than three dollars per person per year. Let’s hope people don’t rashly spend it all at once.

I’ve recently heard Chavez say that Venezuela is protected from the current economic crisis because it has implemented “socialist” policies. But looking at these numbers I can’t help but think Venezuelans better pray that capitalism pulls out of its death spiral and the price of oil starts going back up because if they actually had to live on the output of these “socialist” factories they would truly be sunk.

Ok, I realize this post is excessively snarky and sarcastic. But I hope people can very clearly see the larger point. The point is that while the inauguration of these “factories” might sound impressive when reading about it in a newspaper when you look at the actual numbers you can see they are essentially nothings. Just one aluminum factory built by CAP blows all these factories away by a factor of 10.

Venezuela can’t sit around forever praying for high oil prices — they have to invest and develop other sources of income and wealth. Looking at this, they sure seem to be doing WAY too little.

And of course, looking at these numbers we can see that the notion that Venezuela is somehow well on its way to being socialist, Bolivarian or otherwise, is pure poppycock.

The two articles above first appeared as entries in the Oil Wars blog, a blog kept by a long-time critical supporter of Venezuela’s Bolivarian process: “How Should Venezuela Face the Coming Recession?” (6 January 2009); and “Socialism to the Rescue” (23 February 2009). They are reproduced (edited for readability) here for educational purposes.