Shortly before the websites of the Affordable Care Act went live, Senator Harry Reid called the law “a step in the right direction” (Las Vegas Sun, Aug. 10, 2013). That meant, he said, a step toward improved Medicare for everyone. Is the Affordable Care Act (ACA), often branded Obamacare, a step in the right direction — or the wrong direction?

To answer the question, let’s examine how the Affordable Care Act has affected the health care that people get and the prospects for achieving improved Medicare for All (a single-payer health plan). We also consider the impact of long-term changes in U.S. capitalism.

The major gain from the Affordable Care Act is the extension of Medicaid to approximately eight million new enrollees. Like every concession that might be tossed in, we will not give it up. However, broader eligibility for Medicaid hardly required the elaborate machinery of the ACA. In addition, the expansion of Medicaid rolls has not been matched by an equal increase of resources; every person on Medicaid now has a more difficult struggle getting barebones care than before the ACA.

Insurance Becomes Uninsurance

Most people have heard about, if not experienced, the biggest transformation introduced under Obamacare: the health plan purchasing exchanges, usually accessed at a website in each state. People are driven to them in order to buy federally required health insurance when they do not have it through a job or an established program like Medicare. The problem is that the meaning of being insured has turned into Swiss cheese, riddled with air pockets just when you need a solid bite of actual health care.

The plans from just one vendor, the often-praised Kaiser Permanente system, challenge the buyer to pick the best gamble on her health (see chart below). Following language in the Affordable Care Act, vendors offer plans under metallic labels. Bronze is the most meager health insurance, then silver. Few people can afford the premiums for a gold or platinum plan. Like many vendors, Kaiser offers more than one of each metallic level. One silver plan has a $1,250 deductible (which means you pay all charges in full up to this amount) then a 30 percent copay on inpatient hospital care. The other silver plan has a $2,000 deductible and then a 20 percent copay. Which is better? The buyer must try to guess her health needs for the coming year — because all the plans are degrees of health uninsurance rather than guaranteed care when you need it. Welcome to the casino.

| Source: Tables at healthy.kaiserpermanente.org. Premiums are for females age 50 and age 30 in a northern California ZIP code. |

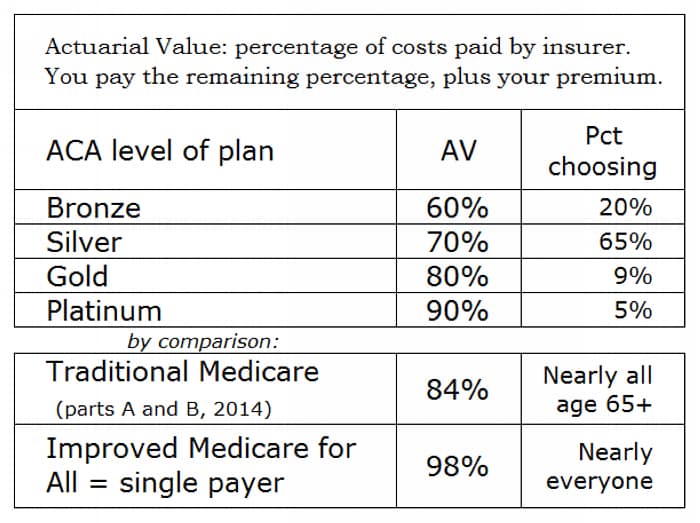

A number measures the Swiss-chees-i-ness of Obamacare plans: the actuarial value (AV). It is defined as the percentage of costs paid by the insurer, averaged over the entire population enrolled in the particular contract. AV is a statistical concept. On average, the so-called insured pay the remaining percentage, plus their premiums.

The Affordable Care Act specifies what shall be the actuarial value of a bronze plan, a silver plan, etc. (see chart below). People who enroll in either of the Kaiser silver plans, for example, will on average bear 30 percent of their health care costs in addition to paying their premiums. The actual percentage will vary widely from one individual to the next; that is the nature of a statistical measure.

| Source: AV levels in Affordable Care Act, Sec. 1302(d)(2)(A). Percent enrollment by metallic level from Dept. of Health and Human Services, Health Insurance Marketplace: Summary Enrollment Report for the Initial Annual Open Enrollment Period, May 1, 2014, p. 8f. AV of Medicare from Daniel W. Bailey, “Actuarial Value and the Actuarial Value of Original A/B Medicare,” In The Public Interest, Jan. 2014, p. 27. Including the Part D drug program, the AV of Medicare is about 60 percent. |

Most people who purchase an individual health policy, if only to satisfy the mandate imposed by the Affordable Care Act, choose a silver or bronze plan. Their actuarial values impose much more financial burden on enrollees than traditional Medicare. In 2014 the AV of Medicare, excluding the Part D drug program, left on average 16 percent of costs to the enrolled senior citizen. The AV of Medicare was higher in the past, but it has drifted down for years. Still, an Obamacare silver plan leaves on average almost twice as much, 30 percent, for you to pay out of pocket, and a bronze plan at a 40 percent out-of-pocket expense is a mockery of being insured.

A real guarantee of a single standard of health care for all, improved Medicare for All, often called single payer, would cover essentially all the cost of health care at an AV of perhaps 98 percent.

The AV levels were watered down in the process of legislating the Affordable Care Act. While it was practically forbidden to mention single payer — prominent physicians in favor of it had to shout at committee hearings and were arrested for doing so — lobbyists for health insurance corporations insisted on lower AVs than the first bills proposed. They got what they wanted.

The Kaiser Permanente operation is an integrated health system. It owns hospitals and employs the physicians, nurses, and other staff who provide the care for Kaiser members. Most health insurance corporations do not have actual resources for care. They write contracts with hospitals, clinics, laboratories, and groups of physicians. The technical term for the people and facilities available under a policy by Aetna, Blue Cross, or whatever is the “network.”

When you choose a policy under the Affordable Care Act, you must examine the network. Health insurance corporations play games with their networks, so you might find that you need to travel a long distance if you need a certain kind of surgery, or sit on a waiting list for many months. Your preferred primary care physician might be in the network when you enroll, but six months later he might not. People are advised to research the network before they sign up with an insurer and annually thereafter, yet investigations find that the network resource lists are often inaccurate. When you grapple with the unknowns of an insurer’s network, you discover another dimension of the uninsurance that masquerades as health care under the ACA.

Insurance corporations manipulate the prescriptions that their policies cover, too. You may find that you cannot get the pharmaceuticals prescribed for you, and the cost of buying them on your own would be thousands of dollars per month (see Kay Tillow, “Health Care Law Did Not End Discrimination Against Those with Pre-existing Conditions.”, MyFDL, March 6, 2015). There is no end to insurers’ tricks for turning health insurance into uninsurance.

The Web exchanges of Obamacare, from their disastrous crashes upon launch in autumn 2013 to the ongoing bitter discovery that the exchanges sell uninsurance, only cover a small percentage of the population. A majority of people, 57 percent of everyone under age 65, still obtain health coverage through someone’s employment — their own, their spouse’s, or their parent’s (Cong. Budget Office, “Updated Estimates of the Effects of the Insurance Coverage Provisions of the Affordable Care Act,” April 2014).

The actuarial value of employer health coverage has declined and the employee has borne more of the cost for decades. The Affordable Care Act intensifies a deep-seated trend. It gives employers an incentive to let the coverage they offer sink toward the bronze and silver levels of Obamacare.

Another provision of the ACA, the so-called Cadillac tax, deliberately attacks job-based health plans that do not join the race to the bottom. Starting in 2018, if an employer provides too generous a health plan, he will be required to pay an excise tax, typically a whopping 40 percent. “Bradley Herring, a health economist at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, . . . estimated that as many as 75 percent of plans could be affected by the tax over the next decade” (Reed Abelson, “High-End Health Plans Scale Back to Avoid ‘Cadillac Tax’,” New York Times, May 28, 2013, p. B1).

The Affordable Care Act is a concerted drive to destroy the social nature of health care, converting it into a commodity purchased by individuals. Health insurance corporations love the ACA for three reasons:

- By selling plans to individuals, the companies can tailor variations to different income levels and other segments of their market, maximizing revenues and profits.

- The ACA compels people by force of law to become customers of health insurance corporations. It is now your individual responsibility to have a health plan, and if you do not, you will be penalized when you file your income tax.

- Third, the federal government subsidizes the insurance corporations by paying part of the premiums for low-income buyers.

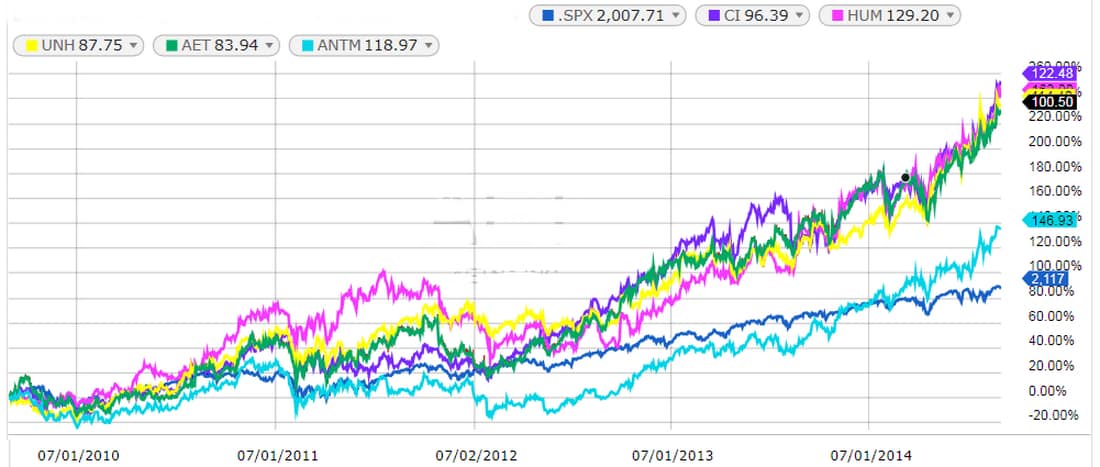

To be sure, insurers, just like drug corporations, hospitals, and other businesses in the health care sector of the economy as well as employers in general, always push the federal government for more favorable regulations. But make no mistake; they love the ACA. Take a look at the stock price of the five largest publicly traded health insurance companies. Before the ACA went into effect, the shares of the different corporations went their individual way. After the ACA passed in 2010, the impact was not immediately certain. In early July 2012, a few days after the first major Supreme Court ruling on Obamacare, the ambiguities were resolved and it was clear that the ACA would be a bonanza. The insurers’ share prices began a long rise, outpacing the Standard & Poor’s index of the 500 largest stocks (see chart below).

| (The blue line is the Standard & Poor’s 500 index. The other five lines, for Aetna, Anthem, Cigna, Humana, and United Health, all climb more steeply than the index from July 2012.) |

Reinforces a Long, Deep Trend in Capitalism

Although the ACA introduced radical new market arrangements, it reinforces a long trend of transforming a relatively secure benefit of good jobs held by the broad middle of the population into individually purchased, insecure, more expensive health care.

The history of the Kaiser organization illustrates the change. The health plan began in 1938 in the remote Washington area where industrial capitalist Henry J. Kaiser had a federal contract to build the Grand Coulee Dam. The workers were members of the plan, but they had to fight to include their spouse and children. The Kaiser health plan expanded during World War Two when Kaiser Shipyards built Liberty ships on the west coast. After the war, Kaiser Permanente served an expanding roster of companies, especially those with unionized workforces. The organization prospered as employment-based health coverage grew in a relatively prosperous era.

A registered nurse who worked for Kaiser in these years told this writer, “We got the men back to work, and management left us alone to do our job.”

Kaiser in its heyday had almost no individually enrolled members. You joined when you got a job that came with Kaiser group coverage. Kaiser also avoided MediCal, the California name for Medicaid. The plan thrived when employers who were engaged in vigorous capital accumulation derived a strategic benefit from keeping a stable cadre of healthy workers. Health benefits tied a core of employees to the firm.

The hourly wage of the median worker peaked in 1973 (Charles Andrews, The Hollow Colossus, p. 10.). Since then, real median earnings have stagnated and declined for an unprecedented forty years, with no end in sight. Employment-based health security, a component of the wage and benefit package, has eroded as part of this trend. An increasing proportion of jobs are low-wage, insecure positions. If the company offers any health plan at all, the employee bears more of the cost of health care in premiums and copays. Some companies merely offer an annual lump sum, the so-called health savings account, leaving each employee on her own to purchase health care. Overall, employers demand more work for less remuneration. You do not get the job if you cannot swallow that fact.

Health coverage purchased by the individual, the essence of the Affordable Care Act, is part of the trend. The Kaiser organization had to become a vendor in the new marketplace. Kaiser added 400,000 new members in California in a year when the ACA went into effect. The organization now must be getting more of its net income from copays and individually-paid premiums, less from per-capita group coverage payments by employers.

The degradation of working people extends beyond the shrinkage of job-based health security that Kaiser exemplified. Medicaid has become more difficult to navigate, and the actuarial value of Medicare for senior citizens, while still well above the bronze and silver levels of the ACA, has been in slow decline for many years.

Who can say that any of this is a step in the right direction?

State Cannot Get Federal Permission for Universal Health Care

When Senator Reid made his claim, he specified the direction. He said the country must “work our way past” insurance-based health care. Perhaps Reid agrees with the general principles of a single payer system:

By a national health program is meant a publicly owned or regulated system that 1) defines a comprehensive package of medical care, and 2) guarantees the package to virtually all residents, regardless of ability to pay. (Charles Andrews, “Concentration Of U.S. Hospitals 1991-1999 and Its Implications for a National Health Program,” Intl. J. of Health Services, 2005, 35:1)

The single payer is the public agency that pays the physicians, hospitals, and other health care providers. The pair of general principles allows for a variety of institutional implementations. The easiest way in the U.S. would be to extend Medicare down from age 65 while shrinking the copays and the Part B (hospital) premium.

Contrary to Senator Reid’s view, Obamacare made it more difficult to achieve a single payer plan. After the Administration forbid consideration of single payer during legislative negotiations for the Affordable Care Act and after defeating the proposal for a public option — a public health insurance plan that would compete with private insurance corporations in the new market exchanges — Congress tossed single payer advocates a crumb. They could work in one or another state for a single payer plan, which would be eligible for a federal waiver from the machinery of the ACA.

Vermont took up the challenge. Activists pushed through legislation in 2011 to set up Green Mountain Care (GMC). It was not really a single payer plan, but it was a universal health care scheme with a high actuarial value.

Without announcing outright opposition, the executive branch of the federal government showed that it would not allow Vermont’s plan to become reality.

Since the federal government subsidizes the premiums of low-income people under Obamacare, Vermont had a right, acknowledged in the ACA law, to the money that the U.S. Treasury would save. Because the state would not have an ACA market exchange, health insurance corporations would not draw subsidies on its residents. Two years ago the Green Mountain Care planners estimated that GMC would qualify for $267 million from the federal government. Late in 2014 federal bureaucrats told Vermont the amount would be a mere $106 million.

All told, Green Mountain Care would need five or six federal waivers. GMC would require a waiver if Vermont wanted to include senior citizens who normally would be in Medicare. It would require a waiver from ERISA, the fundamental law enacted in 1974 that governs employer-provided retirement benefits. GMC also needed arrangements with the federal government for people who move from an ACA state to Vermont or vice versa as well as for businesses that operate in Vermont and outside the state.

Vermont health care planners, the governor, and his staff had thirteen formal meetings in 2014 and countless telephone discussions with federal officials. They met with staff from several bureaus in the Department of Health and Human Services, the IRS (since Obamacare verifies income to compute whether your policy is subsidized as well as enforcing its mandate through income tax penalties), and a variety of other federal offices (Gov. Peter Shumlin, Green Mountain Care: A Comprehensive Model for Building Vermont’s Universal Health Care System, Appendix E-2, Table E-2.1, p. 12f., Dec. 30, 2014 at outside.vermont.gov/sov/webservices/

Shared%20Documents/GMC_Final_Appendices.pdf). Federal waivers were simply not going to happen.

The governor of Vermont shocked state residents and single payer activists when he announced in December 2014 that he had decided to shelve Green Mountain Care. It does not really matter whether he was frustrated by the failure to get federal waivers or whether he just did not want GMC. (Incidentally, Shumlin broadened his reactionary goals and made them explicit when he called for a ban on strikes by teachers while demanding “better outcomes for our students at lower costs.”) The case of Vermont confirms that the Affordable Care Act married health insurance corporations and the federal government. The former want the financial bonanza that ACA brings them. Federal officials are now committed to the alleged success of the ACA, too. They want to show that the system provides “coverage” for millions of people. They want to build careers on managing the apparatus of the ACA (and perhaps go through a revolving door to private health corporations). They scramble to improvise fix upon fix when problems inevitably crop up in a “system” that tries to coordinate health insurance offerings, individual purchases, and a federal mandate. Toss out the entire creaking mechanism and simply expand staid old Medicare to everyone? It is out of the question for insurance executives, federal officials, and technical experts who thrive on the ACA.

The Affordable Care Act strengthened the vested interests opposed to improved Medicare for All. It is the very opposite of a “step in the right direction.”

The Long View Back and Ahead

July 30, 2015 marks fifty years of Medicare. Yet for the last forty of those fifty years, there has been no major reform for working people. After Medicare, the anti-poverty programs of the 1960s, and the clean air and water laws, consumer protection, worker safety and other reforms of the Nader era of the early 1970s, the slate goes blank.

It is not for lack of struggle, protest, and campaigning. The fact is that capitalist accumulation entered a new phase after 1973 (well before modern globalization). Although new industries continue to be born and grow to huge volumes of production, mass creation of good jobs has disappeared. Compare Detroit and Silicon Valley. Detroit “hired millions of factory workers who made automobiles and the steel, rubber, and glass parts that went into them. Electronics, from transistor radios to calculators, through a host of industrial equipment unknown to most of us, to personal computers, digital cameras, cellphones and then smartphones, did not create replacement jobs of standard labor at anything like the same numbers. . . . ‘Detroit’ extended to neighboring states; Silicon Valley is one section of the comparatively small San Francisco Bay Area” (The Hollow Colossus, p. 43. See this book for an explanation of the new contradictions of capital accumulation). The consequence is that capital has less need to concede better wages, including secure health care, and workers have less bargaining strength than they had.

What can we conclude about the struggle for guaranteed, comprehensive health care in the era of the Affordable Care Act? Five principles are clear.

1. Do not support Obamacare; demand improved Medicare for All.

We cannot get to our goal by going down the wrong road. With the proviso that we defend the expansion of Medicaid and a few crumbs from the ACA, we must oppose it rather than pretend that it lays out a path to real health security for all.

2. Fight rising costs and rollbacks of coverage; demand improved Medicare for All.

Attacks on the ACA from the right are part of the drive to dismantle Social Security, land a final blow to trade unions, and drive working people into overt slavery. The answer is not the Democratic Party response of always negotiating for a smaller step in the same direction. We cannot evade the polarization of struggle in the U.S. Obamacare is a failure, and we want improved Medicare for All.

3. Make the fight for Medicare for All part of the general class struggle.

This principle goes beyond organizational advice to link up struggles among different sections of people struggling over health care, the lack of jobs, employer betrayal of pension commitments, and so on. There is a tendency in the single payer movement to portray a universal health plan as a “win-win” in the interest of both working people and capitalists. Single payer is offered as a rational solution that would provide good care while reducing employers’ cost. The strange thing is that capitalists, despite an occasional murmur by a corporate executive, do not buy this line. They know their class interest.

The struggle for health security is part of the general class struggle. We demand the prosperity and equality that this country has the workers, the wealth, and the know-how to achieve. Period.

4. Campaign for the national plan, HR 676; stay out of state swamps.

Vermont learned that the state-by-state strategy is doomed against the resistance of health insurers and other interests newly enriched by the Affordable Care Act. The centerpiece of struggle should be a direct fight to replace the ACA by HR 676, the “Expanded & Improved Medicare for All Act” sponsored by John Conyers and four dozen other congresspersons, which has been in Congress in stable form for many years.

5. Tell it: Guaranteed, equal care for all is now part of socialism, not capitalism.

The project of our era is to go from capitalism to full material equality for all of us — in living standards, in human work, and in health care. We cannot establish a secure, prosperous life under modern capitalism in its latest phase. It is deluded reformism to evade this fact. Our struggles to defeat cuts and push forward in health care, employment, education, housing, and retirement security become stronger with this recognition.

Charles Andrews’ single payer activism began in the campaign for Prop. 186, an initiative on the 1994 California ballot. The author of several titles on political economy, his new book is The Hollow Colossus..