How would you tell the story of your movie Rachel?

My inquiry is rigorous. Since the matter was never brought to trial, I play the role of an investigating judge: I interrogate witnesses, I scrutinize their testimonies, I examine the incriminating evidence, etc. I unravel a mountain of lies and let the truth emerge of itself, without commentary. This type of rigor is essential, because it allows me to go further, to transcend the subject.

In a movie, the result of an investigation counts for less than the investigation itself. The point is to film and to observe places, people, and objects; to gather words, gestures, or silences. To arouse emotions from the coldest and hardest materials, like the images from a surveillance camera or the smooth metal of an autopsy table.

The Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish often said: “The way home is more important than home itself.” It is a very good definition for any artistic endeavor. How one searches and what one comes upon in the process counts for much more than what one finds in the end. In this movie, I tried to inquire poetically.

Some of the images you show are hardly bearable. Was it necessary to show Rachel’s corpse?

Yes. It was necessary to show it, even before the opening credits and several times during the movie so that everything refers back to that image, to the broken body of a young person who will never grow old. My work would not have had any meaning if I had averted my eyes from that image. But it was also important for me to share my difficulty in appropriating it and express the thought process that eventually allowed me to do so. The young man who took one of these photographs says that he felt guilty about it and that he is aware of the element of obscenity it contained. But he took it because evidence was needed. He also says that he regretted not having a video camera, that the presence of a camera might have prevented his friend’s death. I showed excerpts of the movie recently in Belfast, where I was invited to talk about my work in a class with film students. One of the seminar participants, a woman of my generation, said that the images brought her back to her youth, when she was confronting the British army with her bare hands. She added that if she had been killed during these clashes, she would have wanted the image of her blood-drenched body to be shown around the world. Today, there are cameras almost everywhere. Protesters and militants in conflict zones know that if they are killed, the image of their bodies will be given media attention around the world; not only are they not opposed to it, but it is part of their approach. So I believe, very sincerely, that Rachel would have allowed me to use her image; her family, at any rate, did not have any objection.

For me, in fact, the most unbearable moments are the ones when Rachel is alive: when she dances with a Palestinian scarf, or when she writes sentences like: “Coming here is one of the best things I’ve ever done.” I watch those images with a lump in my throat and a wrenching in my gut.

How long did you work on the investigation and on the movie itself? Was it difficult to locate the witnesses and get access to Israeli military officials?

It took approximately three years of research, with travel back and forth between the USA, the UK, and Israel. Nothing was easy, but I’m relentless. The press office of the Israeli army was extremely reticent. These army people are quite helpful and efficient when you’re interested in something they want to talk about, but when you bring up a topic they dislike, they’re very good at making things difficult for you at every step. I harassed them so much that finally, in order to get rid of me, they granted me a 30-minute interview with Maj. Avital Leibovitch, who is the Israeli army’s chief propaganda officer for the foreign press. Not too bad . . . and she even brought some ad hoc documents, with computer renderings she showed on screen.

Rachel’s friends were quite suspicious too, in the beginning, because at the time of the tragedy, a few malicious or incompetent journalists had misquoted or misrepresented them. In addition, they found politically suspect the fact of focusing on the death of an American woman rather than on one of the countless anonymous Palestinian victims. This gave rise to long conversations that ended up establishing relationships based on trust. Rachel’s parents, on the other hand, cooperated with me as soon as we met, but they took a very long time to accept to see me! As for the Palestinian witnesses in Rafah, the problem was not to locate them but to find a way to meet with them; for more than two years, the Israeli army had been turning back all Israeli citizens at the Erez crossing, even those carrying a foreign passport and a press card, even those residing and working abroad, which is my case. Since I could not consider giving up this part of the shoot, the film was in danger of not being made at all. At that point, my faithful director of photography Jacques Bouquin, and my sound engineer Cosmas Antoniadis, saved the day. They decided to go to Gaza without me, in the company of Alexis Monchovet, who knows Rafah very well. Not without difficulty, I managed to obtain the necessary safe-conducts and I directed the segments over the phone. From Tel-Aviv, I spoke to witnesses, guided the camera from afar, asked Jacques to take shots of this or that ruin, this or that place. This experience was doubtless the strangest and saddest I ever went through on a film shoot.

Why don’t you talk about it in the movie?

I don’t like to discuss problems encountered during the shooting of the movie on screen. They are real but remain trivial; it is a little obscene to dwell on them. The constraints placed on a filmmaker’s movement are quite annoying, but they are nothing compared to the sequestering of an entire population. And also, in the end, the film exists and it is more than full. So there is no need to overdo it.

In addition to photographs, you draw on a number of surprising documents, like the implicated soldiers’ depositions or the video shot by a military surveillance camera. How did you obtain these?

The army gave me the military video, which had been carefully sanitized, after many negotiations whose details I will spare you. It does not show the moment of Rachel’s death. As such, it probably wasn’t worth much, but the impact of the sequence comes from the fact that one of the witnesses recognizes himself on the footage because he happened to be wearing a white t-shirt and this creates a little white dot floating about in the frame. As for the depositions, let’s say that I got access to them because it is a small country where I know a lot of people. . . . I had them read aloud by some friends, like my fellow filmmaker Avi Mograbi, whose voice passes very well for that of an officer!

Generally, the material available to documentary filmmakers today is much richer than in the past. Just a few years ago, we had to content ourselves with television archives and press agency photographs, which meant we had to treat subjects that had already received media attention. Nowadays, the smallest events leave traces in a profusion of sources. Rachel’s story is recorded in dozens of amateur videos and photographs, in the emails she sent to multiple correspondents, and in the hard drives of surveillance cameras. It was a lot of work to gather all these sources, but at the time of editing it was thrilling to have so many documents at my disposal.

The driver of the bulldozer and his commandant briefly appear in the movie, in an Israeli television archive. You didn’t interview them yourself. Was this deliberate?

No. I did not manage to meet with them. The army fiercely protects their identity. The driver let me know, through a third person, that he refused to talk to me, and I only film people who accept to be filmed. That archive was produced by a private network for an investigative news show. It was one week after Rachel’s death, at a time when Israeli journalists could still enter Gaza and were welcomed in military bases.

Do you think the driver killed Rachel intentionally?

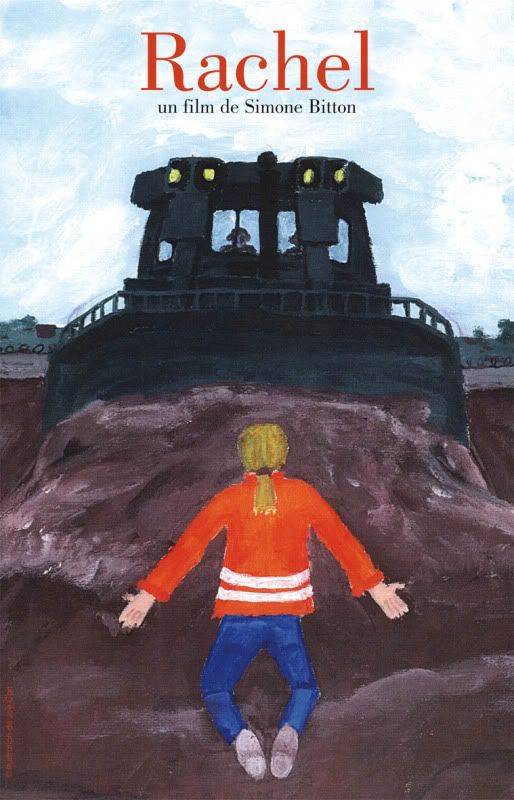

Yes and no. Not in the sense that he coldly decided to crush her or that he received the order to do so. But indifference to human life was a very likely factor. If he truly didn’t see her, it is probably because he didn’t want to. At any rate, the excuse that she was hidden behind a mound of dirt doesn’t hold up: all the photos prove the opposite, and the testimonies are very clear on that account.

A young tank artillery soldier who was posted in Rafah at the time of Rachel’s death describes in the movie, in detail and quite candidly, the extent to which this kind of indifference was the norm. He and his comrades spent their time shooting at inhabited buildings, they gave a hand to the bulldozers destroying homes whose inhabitants didn’t always have enough time to leave.

I don’t mean to point the finger at these soldiers in particular; it is obviously the Israeli army and the occupation system that are to blame outright. The intentional crime my movie addresses is not Rachel Corrie’s death. It is the willful destruction of entire neighborhoods, carried out with the knowledge that people who stay in their homes or attempt to defend them will be killed in the process. One clearly sees where this leads us: six years later, in the same spot, the same army kills hundreds of innocent victims in supposedly targeted bombings. Today the end result has been reached: all Palestinian civilians, as well as anyone seeking to give them assistance, are potential collateral victims; their lives are strictly speaking not worth anything anymore. Talking about war crimes or bringing up the Geneva Convention makes you look naïve, archaic.

There are many young people in the movie, like Rachel’s friends, the witnesses of her death, and that young Israeli anarchist, towards the end, who talks about his struggle against occupation. Do you recognize yourself in them?

Yes, without a doubt. I am fifty-three years old; Rachel could have been my daughter. At her age, I was already protesting against the Israeli occupation, but my generation failed, and today, the situation is even more atrocious. I also feel much sympathy with those who transgress borders, who do not automatically espouse the prejudices of their tribe and who say no to the oppression committed in their name.

Beyond the unraveling of a tragic episode — which in itself harks back to a much larger tragedy — I made this movie for all the young people who inherit this twisted world we leave them and who decide to resist. They are more numerous than we generally think. Rather than growing old and senile, I wanted to go towards them. I discovered that they are braver and more clear-headed than we were, probably because they don’t have a choice. Yonatan, the young anarchist, told me with a smile that one could struggle without hope, that resistance is life, that truth is in rebellion. He doesn’t realize the boundless hope his words, his beauty, and his commitment give rise to!

I come from the Middle East where these things are perhaps more obvious than elsewhere, but this is true for the entire world. To quote Mahmoud Darwish again, I would say that Palestine always becomes a metaphor for the world when one takes a closer look. Once again, I see bombs being dropped on TV and I tell myself that Gaza is not only the grave of Rachel Corrie and of the hundreds of civilians who are regularly assassinated there: it is a universal grave, where humanism as a whole is in the process of foundering.

I am a pacifist who has known many wars, and I am aware that I have made this movie to protect myself from despair. Rachel and her friends have been my human shields.

Simone Bitton, born on 3 January 1955 in Rabat, Morocco, is an Israeli Jewish documentary filmmaker. Among her works are Mahmoud Darwich (1998), Citizen Bishara (2001), and Mur (2004). This interview was conducted in January 2009, and an English translation of it was published on a Facebook page for the film Rachel on 2 February 2009. En français. For more information, contact Les Films du Paradoxe.