| ¿Qué mujer en México, sin importar sus ideas, puede honestamente quedarse callada?

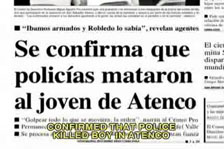

Los días 3 y 4 de mayo del 2006, quedarán en la memoria de los habitantes de San Salvador Atenco, como unos de los días más tristes y violentos de su historia contemporánea. Este pueblo, de unos 33 mil habitantes, dependientes aún de la economía campesina, fue testigo del enfrentamiento violento entre trescientos civiles desarmados integrantes del Frente de Pueblos por la Defensa de la Tierra y unos cuatro mil policías de distintas corporaciones que sometieron al grupo en resistencia y aterrerorizaron al pueblo entero, allanando casas, destruyendo puertas y deteniendo violentamente sin orden de aprensión a 207 personas, incluyendo a niños, mujeres y ancianos, con un saldo final de un menor muerto y veinte personas heridas de gravedad. Lo que empezó siendo un acto de resistencia en solidaridad ante el desalojo de ocho vendedores ambulantes del vecino pueblo de Texcoco, se convirtió en un enfrentamiento violento, que fue presentado por la mayoría de los medios de comunicación, como el “restablecimiento del Estado de Derecho”, ante las arbitrariedades de un grupo radical. La imagen de un grupo de campesinos de Atenco, golpeando a un policía caído, fue transmitida una y otra vez, para justificar la violencia del Estado. El descontrol y la violencia de unos pocos, fueron utilizados para descalificar a todo el movimiento y presentarlo como un peligro desestabilizador para el Estado y el pueblo entero. La agresión contra el policía, debió haberse castigado de acuerdo a la ley, considerando que se contaba con las imágenes necesarias para reconocer a los agresores. Pero en vez de esto, las autoridades estatales y federales, optaron por hacer sentir toda la fuerza y violencia del Estado a personas inocentes, muchas de ellas inclusive ajenas al movimiento que se pretendía desarticular. Los testimonios de hombres y mujeres detenidos que han empezado a darse a conocer por organismos de derechos humanos después del desalojo, nos hablan de un grado de violencia física y sexual que recuerda los peores días de las dictaduras del Cono Sur. ¿Pero por qué tanta violencia contra un grupo de campesinos pobres desarmados? ¿Por qué la violencia sexual contra las mujeres del movimiento? ¿No era contraproducente para el Estado una respuesta represiva precisamente ahora que México ha sido elegido miembro fundador del recientemente creado Consejo de Derechos Humanos de la Organización de Naciones Unidas? Quienes han estudiado los efectos sociales de la violencia y el terror han apuntado hacia las dificultadas que implica el analizarlos y tratar de “explicarlos” desde un discurso académico. El antropólogo australiano, Michael Taussig, señala al respecto que: “Ante las historias de violencia y terror me enfrentaba a un problema de interpretación, hasta que me di cuenta que este problema de interpretación es decisivo para la reproducción del terror, no sólo vuelve muy difícil el poder desarrollar un contradiscurso efectivo, sino que a la vez vuelve mas efectivo lo terrorífico de los escuadrones de la muerte, las desapariciones y tortura, al desmovilizar y limitar la capacidad de resistencia de la gente. Al depender profundamente de la interpretación y el sentido, el terror se nutre a si mismo destruyendo el sentido y la racionalidad”.1 De igual manera la violencia desmedida con las que fueron tratados los detenidos de Atenco tiene el doble efecto de desmovilizar y despertar escepticismo, dificultando la elaboración de un contradiscurso. Este artículo se propone contribuir a la construcción de este contradiscurso, romper el silencio en el que nos ha dejado la indignación y salir de la indiferencia en la que hemos ido cayendo tras la liberación de alguno de los presos políticos de Atenco. Frente de Pueblos en la Defensa de la Tierra (FPDT): Un Símbolo de Resistencia Las representaciones que los medios de comunicación han construido en torno al Frente de Pueblos en Defensa de la Tierra, han enfatizado su carácter violento e intolerante, minimizando su importancia numérica y política y desacreditando sus liderazgos. Estas representaciones tienen poco que ver con los campesinos y campesinas solidarios, alegres e incluyentes, con un alto grado de organización y una profunda reflexión política que me tocó conocer el diez de abril pasado, en la Cañada de los Sauces, en Cuernavaca, Morelos, en uno de los eventos de resistencia multi-clasista, más festivos en los que he estado. En el marco de la celebración de la muerte de Zapata, los adherentes a La Otra Campaña en Morelos, nos encontrábamos esperando la llegada del Sub-Comandante Marcos, en el pueblo de Tetelcingo, cuando se nos avisó que la reunión se trasladaba a la Cañada de Los Sauces, en la colonia residencial de Tabachines, en donde la policía municipal estaba a punto de desalojar a un grupo de residentes e integrantes de grupos ecologistas, que se habían encadenado a los árboles de la cañada para evitar que estos fueran cortados y destruidos en aras de construir un eje vial que pasaría por la zona. La llegada de “La Otra Campaña” a la Cañada, hizo retroceder a las fuerzas policíacas, a las ambulancias, y a la maquinaria pesada que estaba a punto de arrasar con los árboles y sus guardianes. Al poco rato, por la calle principal llegaron unos doscientos campesinos y campesinas de Atenco, marchando de forma ordenada y marcando el paso con el ruido metálico de sus machetes. Venían a solidarizarse con los defensores de la Cañada de Los Sauces, cómo lo hicieron meses antes con los indígenas del municipio de Cacahuatepec, Guerrero que se oponen a la construcción de la presa La Parota, que expropiará sus tierras comunales; ó con los morelenses que enfrentaron a los empresarios de COSCO para defender los murales del Casino de la Selva; ó con los habitantes de Texcoco que se opusieron a la instalación de un Wall Mart frente a las pirámides de Teotihuacan. En todas esas luchas, los campesinos de Atenco estuvieron presentes, compartiendo estrategias y experiencias. Su triunfo en agosto del 2002 cuando lograron la cancelación del proyecto del aeropuerto de Texcoco que pretendía expropiar cinco mil hectáreas de tierras ejidales, los ha convertido en un símbolo de resistencia ante los embates de la globalización. Todas estas luchas locales, comparten una búsqueda de formas alternativas de desarrollo menos depredadoras y más respetuosas de la naturaleza y de la herencia histórica de los pueblos. El triunfo de Atenco, fue un símbolo de que SI SE PUEDE decir “No” a un modelo económico neoliberal, que excluye e ignora los intereses de las mayorías. Este fue el mensaje que el Frente de Pueblos en Defensa de la Tierra, llevó a los habitantes de la colonia residencial de Cuernavaca, animándolos a seguir resistiendo, en sus discursos les dijeron que su lucha en defensa de los Sauces, coincidía con la lucha en defensa de la tierra de muchos pueblos indígenas y campesinos de México. Con sus palabras y sus canciones, fueron rompiendo la barrera de clase que los separaba. El mitin terminó en una gran tertulia popular en la que las amas de casa de Los Sauces, dieron de comer a los asistentes, los trabajadores de Pascual Boing les repartieron jugos, y los campesinos de Atenco alegraron la tarde en un evento musical en el que sus trovadores cantaban corridos sobre sus luchas de resistencia, mientras que las mujeres bailaban de dos en dos chocando los machetes en el aire, en un baile acompasado, ritual que recordaba los bailes religiosos de las comunidades indígenas. Eran mujeres fuertes, extrovertidas, que gritaban consignas y blandían sus machetes con la familiaridad de quien esta acostumbrada a usarlos cotidianamente. No pude evitar pensar en las mujeres zapatistas y en tantas otras mujeres que desde abajo están luchando por la construcción de una vida más justa. Me sentí inundada de su energía política. Nunca me hubiera imaginado que semanas más tarde, estaría viendo a estas mujeres ensangrentadas, humilladas, silenciadas . . . la energía política que sentí ese diez de abril fue el peligro que el gobierno quiso aniquilar. Como estudiosa de los movimientos sociales, quedé impresionada ante el nivel organizativo del Frente de Pueblos en Defensa de la Tierra; ante su capacidad para sistematizar su propia historia de lucha a través de los corridos; ante la fuerza de sus mujeres que tenían un papel protagónico en el movimiento y ante la evidente influencia que estos campesinos tenían sobre los jóvenes estudiantes que estaban en el mitin. Entre la multitud, me tocó ser testigo de un ritual informal de “entrega de cargo” en el que un anciano de Atenco, le entregó a una joven estudiante de Chapingo su machete. Un grupo de jóvenes rodeaban a la pareja y gritaban consignas, mientras que el campesino le dirigía un discurso improvisado a la muchacha, que recibía el machete como recompensa por su solidaridad con las luchas campesinas. Me pregunto si esta joven será una de las mujeres ultrajadas por en la cárcel de Santiaguito, ¿Fue este el costo que pagó por aceptar el “cargo”? En ese momento pensé que era necesario que alguno de mis estudiantes analizara esta experiencia. Tal vez eso mismo pensaron los maestros de los dos estudiantes de la Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia, que ahora enfrentan cargos penales por su presencia en Atenco el 4 de mayo. La policía no entró aquella tarde a la Cañada de Los Sauces y sus habitantes lograron finalmente llegar a una negociación con el gobierno del Estado y reubicar la construcción del eje vial. El costo político de arrasar un fraccionamiento residencial o allanar la casa de un notario, hubiera sido demasiado alto. La represión llegó más tarde en tierras de pobres, en donde aparentemente iba a ser más fácil silenciar las denuncias y desarticular al movimiento en nombre del Estado de Derecho. La Violencia de Estado: Desarticulando el Movimiento Este acercamiento al Frente de Pueblos en Defensa de la Tierra, me hizo desconfiar de inmediato de las imágenes de extrema violencia hacia un policía por parte de algunos de los habitantes de Atenco. Hasta la fecha la prensa no ha dado a conocer los nombres, ni la historia personal de los agresores, pero no es de descartar que el movimiento haya sido infiltrado por provocadores para tener un pretexto para lanzar una campaña represiva. Puede ser también, que la rabia acumulada de tantos años de lucha haya explotado en un incidente de violencia irracional que ha tenido un alto costo para todo el movimiento. No tengo la respuesta a estas preguntas, pero lo que es evidente y hay que seguir repitiendo, es que nada justifica el uso de la violencia policíaca y la violación de los derechos humanos de los detenidos. El mismo poder Legislativo de ese estado, parece haberse adelantado a este tipo de incidentes emitiendo una Ley en febrero del 1994 llamada la Ley para Prevenir y Sancionar la Tortura en el Estado de México, en la que se establece en sus artículos 2do, 3ro y 5to que cómete delito de tortura cualquier funcionario público que “Le inflija al inculpado, golpes, mutilaciones, quemaduras, dolor, sufrimiento físico o psíquico, lo prive de alimentos o agua. Es igualmente responsable el servidor público que instigue, compela, autorice, ordene o consienta su realización, así como quienes participen en la comisión del delito. . . . No se considera como causa excluyente de responsabilidad del delito de tortura, el que se invoque la existencia de situaciones excepcionales, como inestabilidad política interna, urgencia en las investigaciones o cualquier otra circunstancia. Tampoco podrá invocarse como justificación el hecho de haber actuado bajo órdenes superiores.” (énfasis mío Ver www.edomex.gob.mx/ En los desalojos policíacos de Atenco se allanaron y destruyeron casas sin orden de cateo, se detuvieron y encarcelaron 207 personas sin órdenes de aprensión, se asesinó a un menor de edad, se hirieron de gravedad a veinte personas, una de las cuales se encuentra aún en estado de coma; se cometieron veintitrés agresiones sexuales a mujeres, siete de ellas violaciones; La gubernamental Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos (CNDH) ha recibido 150 quejas de los habitantes de Atenco. Ninguna autoridad municipal, estatal ó federal, ha reconocido su responsabilidad en estos hechos y el presidente Vicente Fox se ha limitado justificar el uso de la violencia policíaca “como vía ‘para traer paz a los habitantes de ese municipio ante una embestida de violencia'” (La Jornada, 13 de mayo 2006). De los detenidos el 3 y 4 de mayo, 17 quedaron libres, a 144 se les acusó de ataques a vías generales de comunicación, delito no grave por el que pueden obtener la libertad bajo fianza y 28 de los detenidos, entre ellos el líder del Frente de Pueblos en Defensa de la Tierra, Ignacio del Valle Medina, así como su hijo, César del Valle, han recibido acto de formal prisión por los delitos de secuestro equiparable y ataques a las vías de comunicación. Mientras que la Ley se aplica de manera discrecional a estos luchadores sociales, los responsables de las violaciones a los derechos humanos en Atenco siguen hablando cínicamente en nombre del Estado de derecho. Es importante apropiarnos del discurso gubernamental que habla de aplicar toda la fuerza de la Ley en el caso de Atenco, y presionar por que empiecen por aplicarla a los funcionarios responsables. La Violencia de Género: Sometiendo a las luchadoras sociales Si las mujeres de Atenco blandiendo sus machetes en el aire, se habían convertido en un símbolo de la resistencia campesina, de igual manera sus caras y cuerpos ensangrentados son ahora un símbolo de la ignomia del estado represor que pretende tener el monopolio de la violencia en México. Los testimonios que han salido a la luz pública en las últimas semanas nos hablan de la forma específica que toma la violencia en sistemas patriarcales que siguen viendo a las mujeres como botines de guerra. Tanto la Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos, como el Centro de Derechos Humanos Miguel Agustín Pro A.C. han recogido testimonios directos con las mujeres presas que dan fe de las agresiones sexuales que estas sufrieron. La mayoría de las denunciantes han preferido mantenerse en el anonimato por temor a más violencia, pero las estudiantes extranjeras deportadas: la chilena Valentina Palma, la alemana Samantha Diezmar y las españolas Cristina Valls y María Sastres, han denunciado las agresiones sexuales que sufrieron, así como las violaciones de las que fueron víctimas otras mujeres presas. Los testimonios dados a conocer por los organismos de derechos humanos dan cuenta, no de un caso aislado, sino de una estrategia de agresión sexual que fue fundamental en el operativo policiaco:

Ante estas denuncias la fiscal especializada para la Atención de Delitos Cometidos contra las Mujeres, Alicia Elena Pérez Duarte, de la PGR reconoció que cuando trató de ubicar a las mujeres detenidas los representantes del gobierno del Estado de México, negaron que hubiera mujeres encarceladas. (La Jornada, 12 de mayo del 2006). Este ocultamiento nos habla de una red de complicidades que posibilitaron la estrategia policiaca de terror y hostigamiento sexual. El Secretario de Gobernación, Carlos Abascal minimizó la importancia de estas denuncias y puso en duda su veracidad. Otros funcionarios menores cómo el jefe de la policía regional, Wilfredo Robledo y el portavoz del Departamento del Interior, del Estado de México, Emmanuel Avila, descalificado las denuncias cómo parte de la estrategia legal de la defensa. Mientras tanto los organismos de derechos humanos han señalado que este tipo de delitos se debe de perseguir de oficio, por lo que corresponde al Ministerio Público iniciar la investigación. Es importante aclarar que el mismo Código Penal del Estado de México tipifica el delito de violación en su artículo 273 especificando que: “Comete también el delito de violación quien introduzca por vía vaginal, anal u oral cualquier parte del cuerpo, objeto o instrumento diferente al miembro viril, por medio de la violencia física o moral, sea cual fuere el sexo del ofendido.” Y que en el artículo 274 del mismo código se establece como agravante el carácter tumultuario de la misma, es decir cuando más de una persona participa en la agresión sexual, activamente o apoyando al agresor. Bajo estas definiciones, la experiencias descritas por los testimonios antes citados, no son sólo agresiones sexuales, sino que pueden ser tipificadas como violaciones y como tales deben perseguirse de oficio. La agresión sexual a las mujeres de Atenco viene a engrosar la larga lista de mujeres violadas por motivos políticos en los últimos dos sexenios.3 Para los sectores más conservadores de la sociedad mestiza e indígena, la existencia de mujeres organizadas en alguna comunidad o región se ha convertido casi en un sinónimo de influencia zapatista, aunque esto no sea necesariamente así. Las mujeres organizadas, zapatistas o no zapatistas, se han transformado en un símbolo de resistencia y subversión por lo que han sido el centro de la violencia política. El uso político de la violación sexual fue uno de los puntos que se tocó en la primera fase del diálogo entre el EZLN y el gobierno, en la Mesa Uno sobre Cultura y Derechos Indígenas, que se llevó a cabo del 18 al 23 de octubre de 1995 en San Cristóbal de las Casas. En la Mesa de Mujeres de esta reunión las invitadas del gobierno federal y del EZLN, a pesar de sus diferencias políticas, coincidieron en demandar que la violación sexual sea considerada como un crimen de guerra, de acuerdo a lo establecido por convenios internacionales. Sin embargo, hasta la fecha no se ha realizado ninguna iniciativa para operativizar los acuerdos a los que se llegó en estas mesas de trabajo. Análisis de género en otras regiones militarizadas como Davida Wood en Palestina (1995) o Bette Denich en Sarajevo (1995), señalan que en contextos de conflicto político militar la sexualidad femenina tiende a convertirse en un espacio simbólico de lucha política y la violación sexual se instrumentaliza como una forma de demostrar poder y dominación sobre el enemigo. Atenco no ha sido una excepción, la represión policiaca ha afectado de manera específica a las mujeres cómo nos lo muestran los testimonios antes citados. Desde una ideología patriarcal, que sigue considerando a las mujeres como objetos sexuales y como depositarias del honor familiar, la violación y la tortura sexual son un ataque a todos los hombres del grupo enemigo. Al igual que los soldados serbios, los policías de Atenco “Se apropian de los cuerpos de las mujeres simultáneamente como objetos de violencia sexual y como símbolos en una lucha contra sus enemigos hombres, reproduciendo esquemas de los patriarcados tradicionales, en los que la ineficacia de los hombres para proteger a sus mujeres, controlar su sexualidad y sus capacidades reproductivas, era considerada como un símbolo de debilidad del enemigo” (cf. Denich 1994: 16, traducción mía). A pesar de la efectividad que el miedo tiene en la desarticulación de la resistencia social, es evidente que las mujeres de Atenco están dispuestas a seguir luchando por sus derechos como mujeres y por los derechos de sus pueblos. Sus denuncias ante los organismos de derechos humanos son un contradiscurso que se propone romper el silencio del terror, nos toca a nosotros y nosotras hacer eco de estas voces y demandar que se haga justicia. 1 Taussig, Michael. Shamanism, Colonialism and the Wild Man. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1987, p. 27 (traducción mía). 2 La Jornada 11 de mayo p.8. Para más testimonios de las agresiones sexuales ver también el Informe del el Centro de Derechos Humanos Miguel Agustín Pro A.C “Atenco un Estado de Derecho a la Medida”. www.centroprodh.org.mx. 3 Para un análisis de la violencia sexual en el contexto de la guerra de baja intensidad en Chiapas ver Hernández Castillo, Rosalva Aída “¿Guerra Fratricida o Estrategia Etnocida? Las Mujeres Frente a la Violencia Política en Chiapas” en Witold Jacorzynski (coordinador) Estudios sobre la Violencia. Teoría y Práctica, CIESAS-Porrúa, México D.F 2002. Pp.97-122. |

How can any woman in Mexico, regardless of her ideology, honestly remain silent?

May 3rd and 4th, 2006 will be remembered as some of the saddest and most violent days in the modern history of San Salvador Atenco, on the outskirts of the Mexico City megalopolis. This small town, home to some 33,000 people who still depend on peasant economy, witnessed a violent clash between 300 unarmed civilians, members of the Frente de Pueblos en la Defensa de la Tierra (Peoples’ Front for the Defense of the Land), and some 4,000 policemen from the state and various corporations. The police put the demonstrators down and terrorized the whole community, raiding houses, breaking down doors, and arresting without warrants 207 people, including children, women, and the elderly. At the end of the day, 20 people had been seriously injured and a minor was dead. What had started as a demonstration to support eight street vendors from the neighboring town of Texcoco became a violent clash which most of the media described as the “return to the rule of law” after the arbitrary actions of a “radical group.” The image of a group of peasants from Atenco battering a fallen policeman was shown again and again to justify the State’s use of violence. The loss of control and violence by a few were used to disqualify a whole movement and to characterize it as a destabilizing and dangerous force for the state and the population in general. The attack on the policeman should have been punished according to the law, and considering there were plenty of images of the event, it would have been possible to identify the attackers. Instead, state and federal authorities chose to unleash the full force and violence of the state on innocent people, many of whom don’t even belong to the group the authorities aimed to disband. The testimonies of the men and women arrested on these two days, which are now beginning to emerge thanks to human rights organizations, speak of physical and sexual violence on a par with the worst days of the dictatorships in South America. But why use such a show of violence against a group of unarmed, poor peasants? Why use sexual violence against the women in the movement? Was it not against the state’s own interests to issue such a repressive response, now that Mexico has been chosen as founding member of the United Nations’ recently created Human Rights Council? Scholars who have studied the social effects of violence and terror have pointed at the difficulty of analyzing and “explaining” them from a scholarly point of view. Australian anthropologist Michael Taussig refers to the effect of terror: “The stories of violence confronted me with a problem of interpretation, until I realized that this problem of interpretation is essential to the reproduction of terror: it not only makes it very difficult to create an effective counter-discourse, but at the same time it empowers the terrifying aspects of death squads, disappearances, and torture, because it causes demobilization and limits people’s capacity to resist. Since terror depends so much on interpretation and sense, it ends up feeding on itself by destroying any evidence of sense and rationality.”1 In the same way, the disproportionate violence with which those arrested at Atenco were treated has the double effect of demobilizing and inspiring skepticism about what happened, thus making it difficult to create a counter-discourse, break the silence in which our indignation has left us, and shake off the indifference that has crept after some of the political prisoners were liberated. A Symbol of Resistance: Frente de Pueblos para la Defensa de la Tierra (FPDT) The representations that the news media has constructed around the Frente de Pueblos en Defensa de la Tierra show a movement of a violent and intolerant nature while at the same time minimizing the numbers of its adherents and their politics and discrediting their leaders. These representations bear little resemblance to the men and women I had the opportunity to meet this past April. They appeared a cheerful, supportive, and inclusive group, well organized and capable of complex political thought. I met them just a few weeks before the fateful clash, at La Cañada de los Sauces, in Cuernavaca, Morelos, in one of the most festive, socially inclusive resistance demonstrations I have ever attended. During the memorial festivities of Emiliano Zapata, I was among the supporters of the Otra Campaña in Morelos state, the name given to the tour of Mexico by the Zapatistas (EZLN) during the Presidential campaign, awaiting the arrival of Sub-Comandante Marcos to the town of Tetelcingo. Suddenly it was announced that the meeting was moving to La Cañada de los Sauces, in the residential neighborhood of Tabachines, where police were about to force out a group of residents and environmental activists who had chained themselves to trees. They were protesting the construction of a road that would cross the area and required cutting down the ancient willow trees. The arrival of the Otra Campaña at La Cañada forced out the police, the ambulances, and the bulldozers which were ready to bring down the trees and their guardians. A little while later, about 200 men and women peasants from San Salvador Atenco arrived, marching in order and keeping time with the metallic clatter of their machetes. They came in support of the people of La Cañada de los Sauces, just like they had in previous days supported the indigenous community of Cacahuatepec, Guerrero, who oppose the construction of the a dam that would expropriate their communal land, and the people of Cuernavaca who resisted the construction of a COSTCO store to protect the historical murals of the old Casino de la Selva, or the people of Texcoco who protested the construction of a Wall Mart across from the ancient pyramids of Teotihuacan. The peasants of Atenco supported the struggle of these communities and shared with them their experience and strategies. Their success in 2002, when they managed to stop the government building an international airport that would have expropriated five thousand hectares of farming land, has made them into a symbol of resistance against the blows of globalization. These local struggles share a search for alternative ways of development that are respectful of nature and of the historical heritage of communities. The success of the movement in Atenco was proof that it is possible to say NO to the neoliberal economic model which is indifferent to people’s wellbeing and excludes the majority of them. This was the message that the Frente de Pueblos en Defensa de la Tierra brought to the residents of La Cañada in Cuernavaca, a message that encouraged them to continue resisting. In their speeches, they said that the struggle to defend the old trees of La Cañada was similar to the struggle of many indigenous and peasant peoples in Mexico. The words and songs they brought seemed to melt the barriers between social classes. The meeting became a great popular gathering. The housewives of La Cañada cooked and fed everyone, the workers of the Pascual Boing co-op handed out fruit drinks and the peasants from Atenco enlivened the evening singing corridos about their struggles. The women danced in pairs, clashing their machetes high above their heads in a slow, ritual dance reminiscent of religious dances in indigenous communities. These were strong, extroverted women who shouted out resistance slogans and wielded their machetes with the ease of those who use them in everyday tasks. I could not help thinking of the Zapatista women and of many other women who are fighting from the bottom of society to build a fairer life. I felt inundated by their political energy. I would never have guessed that a few weeks later I would see these same women beaten, bloodied, humiliated, silenced . . . the political energy I felt that evening in April was a danger the government aimed to eradicate. As an analyst of social movements, I was impressed by the organizational expertise the Frente de Pueblos possessed. I was awed by their ability to systematize the history of their struggle in songs, by the strength of the women, who seemed to play a central role in the movement, and by the obvious influence the group had over the young students who were at the meeting. Among the crowd, I had the opportunity to witness an informal “passing of the torch” ritual in which an elder from Atenco gave a young woman student from the University of Chapingo his machete. A group of young people crowded around, cheering and shouting slogans, while the man addressed an improvised speech to the girl, who received the machete in recognition of her solidarity with the peasant movement. I wonder now if that girl was among the women who were raped and abused in the jail of Santiaguito. Could it be that that was the punishment for taking on the “torch”? At the time I thought it would be a good idea to have one of my students analyze this experience. Perhaps that is also what the teachers at the National School of Anthropology and History thought. Two of their students are now facing criminal charges for being in Atenco on May 4th. That afternoon at La Cañada de los Sauces the police stayed away, and eventually the residents were able to negotiate with the government to save the willows. The political cost of upsetting a residential community or breaking through the home of a Public Attorney who lives in that neighborhood would have been too high. But repression came later, in lands of poorer people, where it seems it is easier to silence complaints and break down a movement in the name of the rule of law. State Violence: Breaking Down the Movement My previous encounter with the group Frente de Pueblos en Defensa de la Tierra made me feel suspicious of the images of extreme violence that showed some people of Atenco beating on a policeman. Up to now, the media has failed to give the names or the histories of the attackers, and it is not that far-fetched to think that the movement could have been infiltrated by provocateurs that would then provide the cue to unleash a campaign of repression. It may also be that years of accumulated grief and struggle exploded in an incident of irrational violence for which the movement will have to pay a high price. I do not know what happened, but what is plain and what we have to say over and over again is that nothing justifies police violence, or the violation of the human rights of those taken into custody. The State’s legislature had significant foresight when it approved in February 1994 the Law to Prevent and Punish Torture, which establishes that any public officer who inflicts “blows, mutilations, burns, physical or psychological pain, or who withholds food and water” from a person in custody is guilty of torture, “as is any public officer who instigates, compels, authorizes, orders or consents to the aforementioned. . . . torture is considered a crime and this is not affected by exceptional situations, such as internal political instability, urgent investigations, or other circumstances. Neither can it be excused because it was carried out under superior orders” (emphasis mine, see www.edomexico.gob.mx/ During the police raids in Atenco, houses were broken into and destroyed without search warrants, 207 people were taken into custody without arrest warrants, a minor was murdered, 20 people were severely injured — one of whom is still in a coma (a 20-year old undergraduate student of the National University [UNAM]). There were 23 sexual assaults on women, seven of which were rapes. The National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) has received 150 complaints from residents of Atenco. The authorities, whether municipal, state, or federal, have so far failed to accept responsibility for what happened, and President Vicente Fox has justified the use of violence by the police as “the means ‘to bring peace to the people of this community in the midst of rising violence'” (La Jornada, May 13, 2006). Of those arrested on May 3rd and 4th, 17 were freed, 144 were charged with damage to public property, a misdemeanor for which they can be released on bail, and 28, including the leader of the Frente de Pueblos en Defensa de la Tierra, Ignacio del Valle Medina, as well as his son César del Valle, have been formally indicted under charges of false imprisonment and damage to public property. While authorities use the law at their discretion against social leaders, those responsible for the violations to human rights in Atenco are still shamelessly speaking of rule of law. We need to take the government’s discourse about using the full weight of the law in the case of Atenco and make it our own: we must demand the just punishment of government officials responsible for the abuses. Gender Violence: Subjugating Women Social Leaders If the women of Atenco waving their machetes in the air had become a symbol of peasant resistance, their bloodstained faces and bodies now represent the shame of a repressive Mexican state. The accounts that have come to public light in the last few weeks show the specific form that violence takes in patriarchal systems in which women are still considered war booty. Both the National Human Rights Commission and the Centro de Derechos Humanos Miguel Agusitín Pro A.C. have direct testimonies from the women being held in custody which describe the sexual attacks they suffered. Most of the victims have preferred to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals, but the deported foreign students — Valentina Palma from Chile, Samantha Diezmar from Germany, and Christina Valls and María Sastres from Spain — have denounced the sexual assaults they suffered, as well as those other women were subjected to. The testimonies made public by the human rights organizations show that the attacks were not isolated cases but rather a strategy of sexual violence which was a key part for the police operation:

Alicia Elena Perez Duarte, the special attorney in charge of crimes against women, said that upon hearing about these testimonies she tried to get in touch with the women held in custody, but the representatives of the government of the locality said there were no women in custody (La Jornada, May 12 2006). This lie points to a web of complicities which made possible a police strategy of terror and sexual violence. Marinana Selvas, an anthropology student among the 28 activist still in jail, has contended that the Public Attorney’s rejection to consider the testimonies of rape is a strategy to allow time to erase any physical evidence of the sexual abuses. This contention has probably put her at risk as she is still under arrest. Carlos Abascal, the Secretary of State, minimized the relevance of the women’s complaints and doubted their veracity. Other lesser officials, such as the regional police chief, Wilfredo Robledo, and the Speaker of the Department of State of the Estado de Mexico, Emmanuel Ávila, disregarded the testimonies as part of a legal defense strategy. Meanwhile, the human rights organizations have pointed out that this type of crime is prosecuted by the state, so it is the job of the Public Attorney to initiate the investigations. The criminal law of the state of Mexico, in which the raids took place, defines the crime of rape in Article 273 by specifying that “also guilty of rape is the person who by force, whether it be physical or moral, introduces any part of the body, object or instrument other than the penis in the vagina, anus, or mouth of the victim, regardless of gender.” Article 274 of the same law establishes that the participation of multiple attackers, that is, more than one person taking part or supporting the aggressor, constitute an aggravating factor. Under these definitions, the experiences described in the testimonies are not just sexual assaults, but rape, and as such should be prosecuted by the state. The attacks on the women of Atenco add to the long list of women who have been the victims of sexual violence for political motives in the last two presidential terms.3 For the more conservative sectors of Mexican society — both mestizo and indigenous — any show of organization among women in any community or region has become a synonym of Zapatista influence. Organized women, whether they are Zapatistas or not, are a symbol of resistance and subversion, and for that reason are placed at the center of political violence. The political use of sexual violence was one of the issues discussed during the first series of talks between the EZLN and the government on October 1995, in San Cristóbal de las Casas. At the Women’s Table during this meeting, the people invited by the government and those brought by the EZLN agreed, in spite of their political differences, that rape should be considered a crime of war as described by international law. There have been no efforts, however, to act on the agreements reached then on those negotiation tables. Gender analysts from other militarized regions, such as Davida Wood in Palestine or Bette Denich in Sarajevo, point out that in contexts of political military conflict feminine sexuality tends to be transformed into a symbolical space of political struggle and rape is instrumentalized as a way of showing power and dominion over the enemy. Atenco was not an exception: police repression has affected women in particular, as we can readily see from their testimonies. In a patriarchal ideology that still considers women sexual objects and repositories of a family’s honor, the rape and sexual torture of women constitutes a way of attacking all the men on the enemy’s side. Just like Serbian soldiers, the policemen of Atenco “take possession of women’s bodies one after another, as objects of sexual abuse and as symbols in a fight against their male enemies, thereby reproducing traditional patriarchal patterns where the male inability to protect their women, to control their sexuality and their reproductive capacities, is considered a symbol of weakness in the enemy.” In spite of the effectiveness of fear as a disintegrator of social resistance movements, it is evident that the women of Atenco are determined to continue fighting for their rights as women and as members of a community. Their testimony before human rights organizations proposes a counter-discourse that can break the silence of terror. It is our turn to echo their voices and demand that justice be done. 1 Taussig, Michael. Shamanism, Colonialism and the Wild Man. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1987, p. 27 (translation mine). 2 La Jornada, 11 May 2006, p.8. For more testimonies of the sexual aggressions, see, also, the report of el Centro de Derechos Humanos Miguel Agustín Pro Juárez: “Atenco un Estado de Derecho a la Medida.” 3 For an analysis of sexual violence in the context of low-intensity warfare in Chiapas, see Hernández Castillo, Rosalva Aída “¿Guerra Fratricida o Estrategia Etnocida? Las Mujeres Frente a la Violencia Política en Chiapas,” in Witold Jacorzynski (ed.), Estudios sobre la Violencia: Teoría y Práctica, CIESAS-Porrúa, México D.F 2002. Pp.97-122. |

| ATENCO: ROMPER EL CERCO [ATENCO: BREAKING THE SIEGE] (Produced by Canal 6 de Julio and Promedios) Click on any of the images below to watch the documentary. |

|

|

|

|

R. Aída Hernández Castillo is Associate Professor of Social Anthropology at the Center of Advanced Studies in Social Anthropology (CIESAS) in Mexico City. She is the author of Histories and Stories from Chiapas: Border Identities in Southern Mexico (University of Texas Press, 2001) and a co-editor of Mayan Lives, Mayan Utopias: The Indigenous Peoples of Chiapas (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2003) and Dissident Women: Gender and Cultural Politics in Chiapas (University of Texas Press, 2006). This essay, translated by María Vinós, first appeared in English in Socialist Project’s E-Bulletin The Bullet (No. 24, 9 June 2006). The original essay in Spanish “Violencia de Estado, Violencia de Género en Atenco” (23 May 2006) was published by G-México, Agencia Latinoamericana de Información y Análisis-Dos (Alia2), Cheapas Peace House, and Red Voltaire among other Web sites.