Yes, the big economic crisis is hitting Germany, too. The evidence includes the hasty meetings of top politicians and the decision by the government coalition of Christian Democrats and Social Democrats to save the suffering banks with 500 billion Euros in credit.

Another piece of evidence: Karl Marx’s famous book Das Kapital is selling better than it has for years; its main publisher has already sold 1,500 copies in 2008; in the past, at the very most, it sold 500 for an entire year. More people seem to be hunting for explanations and even solutions. (But the publisher warned that for laymen the book might be “rough going”.)

A third piece of evidence: employees of the Opel auto plant in the East German town of Eisenach are now working only four days every two weeks. Opel belongs to General Motors which, we hear, is not having an easy time either. I still recall the joy of many Eisenach workers nineteen years ago when they got the chance to work for such a famous and giant company — and to buy its cars.

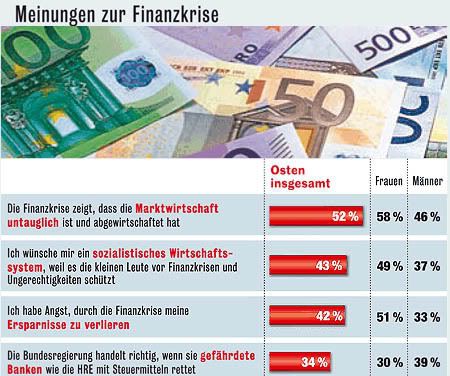

An even more curious bit of evidence: a recent poll of East Germans by a major magazine found that 52 percent had lost all confidence in the free market economy while 43 percent would support a return to a socialist economy.

Most of those interviewed for the accompanying article agreed. Looking back to GDR days, one 46-year-old worker from East Berlin said, “In school we read about the ‘horrors of capitalism’. They really got that right. Karl Marx was on the ball. . . . I had a pretty good life before the Wall fell. No one worried about money because money didn’t really matter.” A retired blacksmith said: “The free market is brutal. The capitalist wants to squeeze out more, more, more.” And a city clerk added: “I don’t think capitalism is the right system for us. . . . The distribution of wealth is unfair. We’re seeing that now. The little people like me are going to have to pay for this financial mess with higher taxes because of greedy bankers.” Another Easterner recalled being delighted about the fall of the Berlin Wall and capitalism replacing communism. But, he added, “It took just a few weeks to realize what the free market economy was all about. . . . It’s rampant materialism and exploitation. Human beings get lost. We didn’t have the material comforts but communism still had a lot going for it.”

Such sentiments show up in the ballot boxes. The young party called The Left (Die Linke), whose origins trace back largely to the former ruling party of East Germany and whose program, despite many alterations, still calls for socialism, won second place in four out of five East German states, is the strongest party in East Berlin, and, currently, leads polls of all East Germany. Since joining with a left-wing party in West Germany, it is slowly but steadily spreading there as well.

All this is worrisome, indeed, downright alarming for the four parties which have hitherto ruled the German political roost. But they are not abandoning the fortress of free enterprise capitalism by any means, crisis or no crisis.

Almost every evening one or the other German TV channel explains to viewers how terrible life in the GDR used to be. Sometimes several channels compete in taking on this job. Two constant themes, of course, are the terrors of the Stasi and the horrors of the Berlin Wall. But there is also variety: how really bad GDR child care centers were, how athletes were made to suffer, how vacationers were regimented, how corrupt the big shots were, how poor the music, how heavily censored the books, plays, or films. This enlightenment is often offered in the form of historical reportages, sometimes we are treated to full-length dramas and feature films, some of them very well-made. Similar message are inserted in the form of clever barbs into even the briefest, seemingly irrelevant news items.

Some of the facts are undoubtedly correct. Many of the private impressions are certainly genuine. There was far more than enough bureaucracy, dogmatism, repression, and injustice during the forty years of the German Democratic Republic. But three things strike me when I watch these programs or, more and more frequently, turn them off after a few minutes.

Although they sometimes try to hook an audience by sounding impartial, admitting, often slightly sarcastically, that after all there may have been a few acceptable elements in GDR life, even then the overwhelming message soon reverts to the usual extremely bleak picture full of all the clichés, ignoring the many aspects of life which were very normal and could even be quite pleasant. But it is just such a mix of good and bad factors that I observed during the 36 years I lived in the GDR, participating in everyday life as an apprentice, a worker, a student, and a journalist who visited nearly every nook and cranny of the country and spoke, publicly and very privately, with people from all walks of life. But the media prefers bashing and smashing, the rest is barely hinted at, and the media provides virtually no opportunities to talk back.

It may seem a mystery why programs telling us how tough we had it in those years of misery are not diminishing in number or ferocity, although the GDR has been dead since 1990. Why do they insist so very long on kicking a dead horse?

The aforementioned opinion poll makes the answer more obvious than ever. True, the demise of the GDR in 1990, officially called German reunification but referred to by many as “annexation,” did bring a wide array of hard-to-get or unknown consumer goods, from bananas and kiwis to BMWs and ocean voyages. World travel became possible, retail trading expanded, houses were renovated, cafes multiplied, road traffic and advertising, from neon lights to TV commercials, virtually exploded. A certain percentage of the people certainly lived and still lives better than before, perhaps about one third.

But very many paid a heavy price, which is now being worsened by the new financial and economic crisis. Millions of jobs were lost after 1990 when East German factories were priced out of existence or bought up by western competitors for a song and soon shut down. Unemployment remained steady at double western levels (it is now about 14 percent), and wages and pensions stayed just as consistently below West German levels, often 30 percent below.

Very gradually, a few areas began to pick up a little — some resort areas along the Baltic, a few auto and electronic plants, for example. But other factors worsened. Medical care became more and more expensive. Fees climbed or threaten to climb for child care and education. Taxes, except for the wealthy, moved upwards. Pensions, worth less and less, are now set at 67 (in the GDR men received pensions at 65 and women at 60). Worst of all, there is little or no security. Even those working for the few famous and established companies which did open up East Germany plants never know when their jobs will be terminated; a friend of mine lost hers exactly on her 50th birthday. For those laid off after the age of 45 or 50, it is extremely difficult to find a new job, and after a year with jobless pay the relief sums granted reduce their recipients to poverty and virtual subservience. And now, while the situation has not yet reached USA proportions, homelessness is also spreading. Is it any wonder that people recall GDR days when jobs were secure and evictions were prohibited by law?

But all that was known as “socialism.” The very thought of such recollections frightens the powerful forces controlling the three main parties and greatly influencing the fourth, the once progressive Greens. Some years ago a Social Democratic cabinet minister demanded the “de-legitimizing of the GDR.” Every trick in the book, every propaganda device is being thrown into the fight. A major battleground is the school system where, unlike TV, there is some dialogue. Leading politicians complain constantly that East German pupils are “unclear about recent German history” and that, instead of listening to what teachers are ordered to teach them or what the new textbooks preach, they are often influenced by what parents and grandparents tell them about life in the old days, not only the bad but also the good. The politicians almost hysterically demand ever more forceful methods and ever more one-sided textbooks, now for the coming anniversaries of the founding of the two German states (1949) and the “Fall of the Wall” (1989). Who will win this tug-of-war? Or rather, who will gain more ground? The next elections, on state and national levels — and maybe a few protest demonstrations or strikes — could provide some answers.

Victor Grossman, American journalist and author, is a resident of East Berlin for many years. He is the author of Crossing the River: A Memoir of the American Left, the Cold War, and Life in East Germany (University of Massachusetts Press, 2003).

|

| Print