Introduction

Despite the vast literature examining the link between trade liberalization and economic growth, empirical studies still fail to provide conclusive and unequivocal evidence supporting the link. What most of these studies emphasize is that openness, accompanied by a country-specific mix of appropriate complementary policies (macroeconomic and financial policies, education, infrastructure, institutional capacity and governance), plays a significant role in promoting growth.

The jobs claims-higher wages model has often been used by adherents of free trade to argue for deeper integration and greater openness in trade and financial markets. In fact, neoliberal economists and the major actors in the global governance of trade, i.e. the World Trade Organization (WTO), the World Bank (WB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), prescribe or impose a one-size-fits-all deregulated export-led growth and development strategy for developing countries. More often, developing countries have to swallow the bitter pill of full liberalization in exchange for loans from the WB-IMF and in getting more market access in developed countries as well.

Similarly, trade liberalization is believed to lead to higher wages via price transmission. Reducing the after-tax or -tariff prices of imports immediately reduces the prices of imported goods and import substitutes, thus increasing real incomes. On the employment side of the equation, since “a tariff reduction lowers the marginal cost of production by reducing the cost of imported materials” (Saito and Tokutsu, 2006:17), thereby encouraging and expanding production, this purportedly increases the demand for labor.

But does a regime of free trade create good jobs and increase wages in relative and real terms? Does free trade raise living standards in the long term? In developing countries such as the Philippines where the domestic currency is weak or of low quality and where the current account deficit, high indebtedness, and weak labor organizations, constitute its economic constellation, the twin argument that free trade creates jobs and leads to higher wages leaves much to be desired. Markets cannot be relied upon to replace lost employment. In an economy where there is high uncertainty, one cannot rely on the logic of the market to correct deficiencies, mismatches, and inequalities.

Challenging the dominant economic paradigm that drives today’s process of globalization and the neoliberal theoretical assumptions linking trade liberalization to growth is thus the area of theoretical debate where this research seeks to engage in. In this regard, this paper argues that greater openness through stronger trade and capital account liberalization in an import-dependent and debt-ridden economy to a large extent, as well as a confluence of other factors both external and internal, took toll on growth, employment, and wages, and even exacerbated the economic crises in the Philippines during the period.

Does Trade Liberalization Lead to Economic Growth?

Debunking the Free Trade Myth

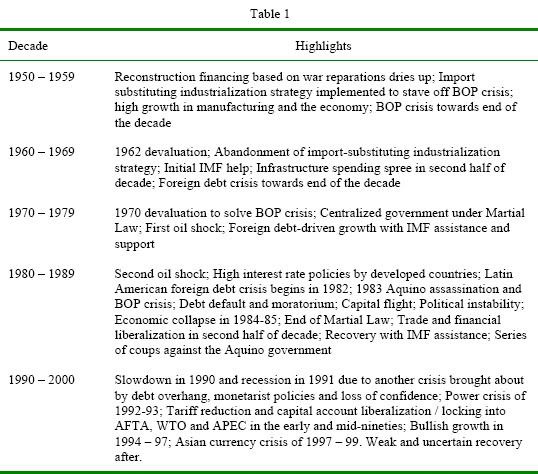

Table 1 provides highlights of the Philippine economy between 1950 and 2000. Note that in each of the decades prior to the 1980s, there was at least one crisis hitting the Philippine economy, i.e. the balance of payments (BOP) crisis in the 1950s, the foreign debt crisis in the 1960s, and the BOP crisis in the 1970s. The IMF came into the Philippine economic picture in 1962 when the country sought IMF help to ease the pressure on the balance of payments by a peso devaluation in 1962 (from 2.02 to 3.85 pesos per dollar). Henceforth, the IMF would be instrumental in designing economic policies for the country within the context of the Washington Consensus.

Source: Lim and Bautista, 2002.

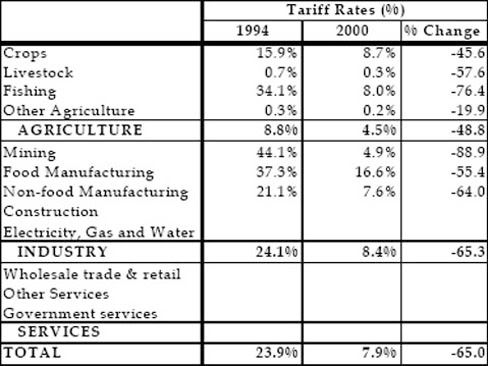

As shown in Table 1, it was however in the decades of 1980 to 2000, the period of rapid external liberalization under the World Bank-IMF’s Structural Adjustment Program, that the country experienced economic collapse, intense recession, and stagnation. The period 1980-2000 was highlighted by increased frequency and depth of bust-recovery cycles amidst tariff reduction and capital account liberalization that led the country’s participation in the Asian financial crisis.3 Table 2 shows tariff reductions in various sectors between 1994 and 2000.

Table 2. Tariff Rates

Source: Cororaton (2003:5), Table 1.

Specifically, it was during the period 1993-1996 that trade liberalization, which was started in 1986, was vigorously pursued by locking the country into international trade regulation and deeper integration through the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) in 1993, the WTO, and the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). During this period, the government completely lifted all import restrictions and pursued genuine tariff reduction. Moreover, full capital account liberalization was achieved in 1993 after being initiated in 1991 through the passage of the Foreign Investments Act. In 1992, foreign investors were free to repatriate their capital. These reforms made easy the entry and exit of foreign capital, largely in the form of short-term debts and portfolio investments (unhedged dollar borrowings or “hot money” used to finance real estate, construction, speculative and manufacturing activities), setting the stage for the participation of the Philippines in the Asian financial crisis.

A regime of low tariffs and export orientation was believed to foster sustained economic growth. Using ratio of trade (imports plus exports) to GDP (Dowrick & Golley, 2004:40) as a measure of “revealed openness”4, Table 3 reveals a movement towards more openness in the Philippines from 1960 to 1999: total trade as a percentage of GDP leaped from 21 percent in 1960 to 101 percent in 1999. Note too in Table 3 that the total trade increase between 1980 and 1999 (49%) was higher than the period between 1960 and 1980 (31%). The dramatic rise of manufactured exports in the Philippines beginning in 1981 indicates the deepening of a free trade regime in the economy.

| Total Trade (imports+exports) (% of GDP), Philippines Year Total Trade (% of GDP) |

|

| 1960 | 21.02 |

| 1970 | 42.62 |

| 1980 | 52.04 |

| 1990 | 60.80 |

| 1999 | 101.37 |

Increasing Frequency of Bust-Recovery Cycles in 1980-2000

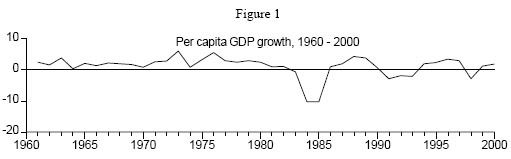

According to Lim and Bautista (2002), the period 1980-2000, during which reforms further liberalizing trade and the capital account were undertaken, was marked by increasing frequency and depth of bust-recovery cycles (Figure 1) in the Philippines pointing to a more volatile movement and a seemingly shorter cycle length compared to previous periods. Thus stronger external liberalization pursued in the second half of the 1980s has been accompanied by increased volatility and frequency of recession-recovery (or bust-boom) cycles. As a corollary, the country’s dependence on imports and unsustainable (private and short-term) foreign capital flows (or “hot money”) has been attributed to periods of more frequent and shorter growth and recession cycle and the lack of macroeconomic development (Lim and Bautista, 2002).

Source: Lim and Bautista, 2002.

In the light of the above, it was only in the period 1980-2000 — aptly termed as the “lost decades”5 — when trade and capital account liberalization went into full swing that the Philippines experienced negative growth. From a 66 percent rise of real per capita GDP (in 1985 US$) in the period 1960 to 1980, this plummeted to -1 percent in the period 1980-2000, or a decrease of 67 percent (CEPR, 2000). The forgone increase in per capita GDP during the “lost decades” was estimated at 68 percent. The fall in growth rate in the case of the Philippines and other developing countries affirms the findings of Weisbrot et al (2001) that the decades of 1980-2000 — the period of globalization marked by increased openness to international trade and financial flows — merely brought stagnancy and diminished progress to the developing countries.

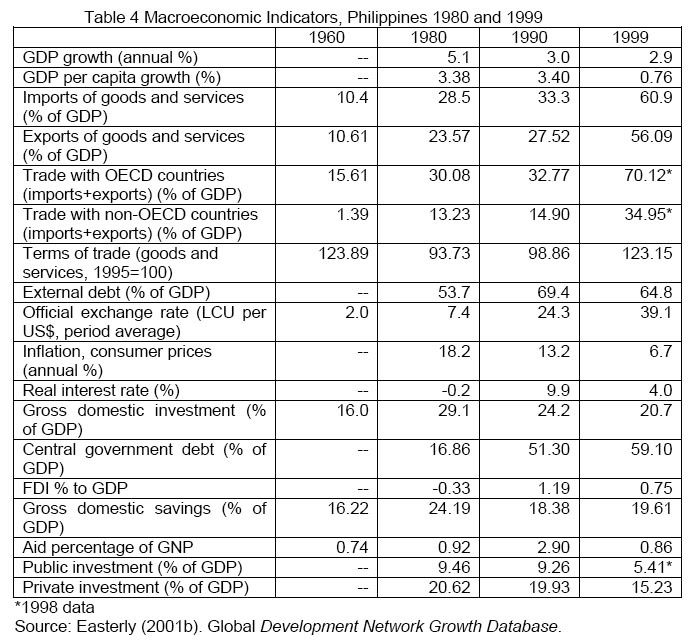

Indeed, the macroeconomic indicators in Table 4 are telling of the arrested growth experienced in the Philippines during these lost decades. GDP growth rate plummeted to 2.9 percent in 1999 from a high of 5.1 percent in 1980. In effect, GDP per capita slid down to almost a negligible 0.76 in 1999 from 3.38 percent in 1980. (A 3% growth in per capita is the minimum rate believed to be necessary for a developing country to make a dent in poverty.6)

Table 4 also indicates the import dependency of the Philippines as growth in imports (60.9% in 1999) as a percentage to GDP outpaced exports (56% in 1999). This is despite the huge devaluation of the peso (per US$) from 7.4 in 1980 to 34.10 in 1999. Moreover, the data reveal that OECD countries are still the major trading partners of the country. Although the terms of trade (TOT)7 improved between 1980 and 1999, the 1999 TOT (123.15) was still below the 1960 figure of 123.89.

External debt meanwhile increasingly ate up a bigger share of the country’s gross output, from 53.7 percent of GDP in 1980 to almost 65 percent in 1999. And despite the avowed lure of foreign direct investment (although FDI merely accounted for 0.75% of GDP in 1999) crowding in domestic investment, the latter (as percentage to GDP) dropped to about 21 percent in 1999 from 29 percent in 1980. Public and private investments declined too as gross domestic savings diminished from 24.1 percent (of the GDP) in 1980 to 19.6 in 1999, despite a substantial decline in inflation rate (from 18.2% in 1980 to 6.7% in 1999).

One may ask why growth stagnated or declined despite the robust performance of the export sector (from 23.57% in 1980 to 56.09% of GDP in 1999) in the period 1980-2000. Easterly (2001a) speculates that worldwide factors like the increase in world interest rates, the increased debt burden of developing countries, the growth slowdown in the industrial world, and skill-biased technical change may have contributed to the developing countries’ stagnation. But what is certain that even World Bank economists such as Easterly recognize is that the stagnation of developing countries during the “lost decades” was a major blow to the optimism surrounding the Washington Consensus. Moreover, as Stiglitz (2006:16) attests, the IMF had already conceded in 2003 that, at least for many developing countries, capital market liberalization did not lead to more growth but to more instability. Unfortunately, this acknowledgment came after capital market liberalization’s devastating effects in many developing countries.

Free Trade and Arrested Growth: the Export Structure Difference

Although external liberalization may provide the needed stimulus for growth, the structure or composition of an economy’s exports lies at the crux of the trade-economic growth calculus. Akyuz (2005) explains that:

Trade statistics showing a rapid expansion of technology-intensive, high value-added exports from developing countries are misleading because of double-counting of trade among countries linked through IPNs [international production networks]. Such products appear to be exported by developing countries, but in reality those countries are often involved only in the low-skill, assembly stages of production, using technology-intensive parts and components imported from more advanced countries. As trade flows are measured in gross value rather than value-added, imported parts and components are counted among the exports of the countries assembling them.

Such is the case of the top two exports of the Philippines — electronics/semiconductors and garments. Notably in electronics manufacturing, most of the technology and skills are embedded in imported parts and components so that much of the value-added accrues to the producers and transnational corporations in the more industrialized countries where these parts and components come from.8 It is in this regard that Akyuz’s (2005) comment that it is labor itself rather than the product of labor that is exported finds justification.

Structure and Composition of Philippine Exports

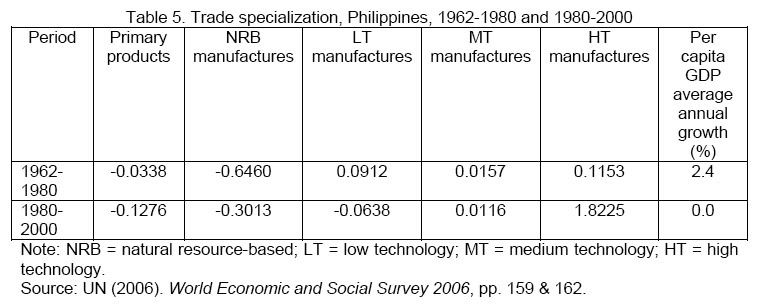

To date, high technology manufactures (HT)9, particularly electronics and semiconductors components, dominate the export structure and specialization pattern in the Philippines both for the periods 1962-1980 and 1980-2000 (Table 5). Electronics is the country’s top export, contributing to 68 percent of total export earnings.

The Philippines’ export participation in HT manufactures is through IPNs involving mere assembly of components that utilizes labor, the most abundant and least mobile factor and thus the least contribution to value added. Data from the National Statistics Office (NSO, 2002) reveal that census value-added of electronics components was a mere 15.8 percent of the total value in 2001.

Thus, like the garments exports10 (low-technology manufactures) albeit to a much lesser extent, electronics exports have high import content. In this regard, “strong increases in the manufacturing exports of developing countries — particularly those participating in IPNs — may have taken place without commensurate increases in incomes and value added” (UN, 2006:75). Thus despite the marked increase in HT manufactures specialization in the period 1980-2000, there was no growth in per capita GDP (Table 5).

In the case of the garments industry, the second top export of the Philippines, the Multi-Fibre Agreement (MFA) may have locked the economy into its designated area of specialization in the garments’ IPNs. The temporary benefits derived from the preferential treatment under the MFA sidetracked the country from diversifying its economy or improving upon the competitiveness of the industry to make it viable even after the end of the quota regime.

Does Free Trade Create Jobs? Challenging the “Jobs Claims” Model

There is an abundance of economic literature pointing to the positive impact of trade liberalization on employment and wages. Where a tariff reduction does have a non-negligible impact on wages and levels of employment, neoclassical economists argue that any adverse effects, i.e. flooding of cheaper imported goods, can be wiped out by a tariff reduction’s effect on input prices that induce a reduction on domestic prices.

However, the picture is more nuanced and less sanguine. In an export-oriented economy where high value-added inputs are mostly sourced abroad for both tradables (exportables) and nontradables, tariff cuts may in fact adversely affect the terms of trade. In the case of the Philippines, a simulation study of abolishing existing tariff payments by the Saito and Tokutsu (2006) shows the direct effect of tariff cuts: that although the demand for exports tend to increase following a relatively large tariff reduction, the trade balance worsens as the demand for imports more than doubles the demand for exports. This is disastrous in an export economy like the Philippines which is very much import-dependent.

Akyuz (2005) critiques as bereft of reality simulations done by the World Bank highlighting the benefits that developing countries could reap from further liberalization in the Doha Round. These studies use “general equilibrium models” that assume automatic market clearing, rapid redeployment of resources, and full or equal employment after liberalization. To Akyuz, factors of production, including labor, capital, and land are often sector- or product-specific. Moreover, “expansion in sectors benefiting from liberalization requires investment in skills and equipment, rather than simply reshuffling and redeploying existing labor and equipment.” Thus, like the case of the Philippines, the immediate impact of rapid trade liberalization could be unemployment, deindustrialization and growing external deficits despite a significant increase in export growth.

Ranney and Naiman (1997) stress that the “jobs claims” argument for a deregulated export-led growth strategy focuses only on exports neglecting the fact that there are negative impacts on jobs and wages if imports are higher than exports. Like Akyuz (2005), they argue that a deepening of free trade does not necessarily create jobs in the light of the following:

- In a deregulated economy, there is no incentive or requirement for firms to use their profits to the benefit of the people. There is no guarantee that if a firm or a country becomes more efficient and increases exports this will automatically increase jobs and wages and lower prices.

- The argument that increased exports lead to employment and income gains does not consider that unregulated corporations can and do use employment from exports for activities resulting in employment and income losses for many workers, i.e. investment in labor-saving machinery, mergers, and acquisitions.

- Global firms that gain export market shares often find it more profitable to locate nearer to their market. They seek lower wages elsewhere. Moreover, increased imports due to the lowering of trade barriers could displace domestically produced goods and services.

- The argument that in a deregulated export-led growth job losses in the “restructuring” process result in greater efficiencies and that new jobs with higher wages will replace old ones is flawed. This assumption is based on a situation of full employment. The market is seldom able to replace lost employment with comparable jobs. Even if new jobs were created, people who lose jobs often do not get the new ones. Moreover, many of the replacement jobs are of inferior quality. It should be likewise noted that higher wages in the export sector could be due to high unionization, labor shortages in specific occupations, or higher productivity.

- Imports may depress wages too in certain industries and occupations.

In sum, Ranney and Naiman emphasize that that the net effect of free trade must take into account both imports and exports.

Employment and Labor Productivity Effects of External Liberalization

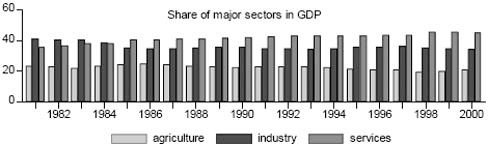

It can be seen in Figure 2 that during crisis periods, the share of industry to GDP is on the decline while the opposite holds true to the services sector. Note that industry had the highest share until 1984 but was subsequently overtaken by the services sector and has never regained its position.

Figure 2

Source: Lim and Bautista (2002).

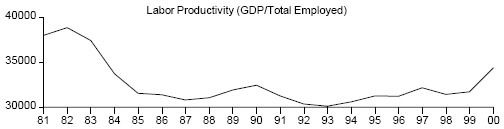

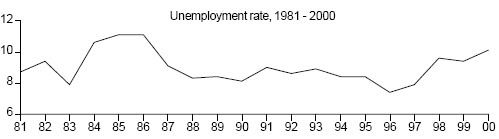

Similarly, the trend in overall productivity follows the changes in economic activity; it declines if the economy is in a crisis period (Figure 3). Meanwhile, the unemployment rate was declining in the recovery years but started rising during economic slowdown (Figure 4).

Figure 3

Source: Lim and Bautista (2002).

Figure 4

Source: Lim and Bautista (2002).

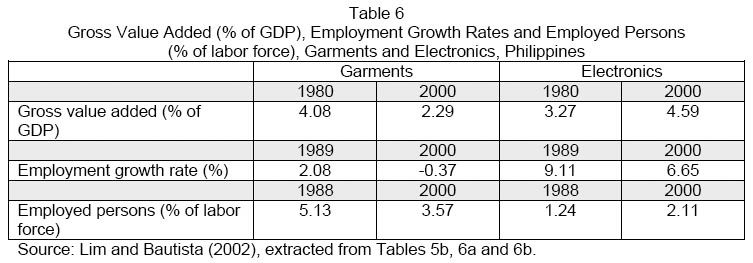

The high import intensity of electronics-semiconductors and garments sectors in the Philippines has very low value-added and employment impact in the economy. In 2000, for example, these sectors generated a meager 6.9 percent of total gross value added and 5.7 percent of total employment (Table 6). In fact, these figures were even lower compared to earlier years — in 1980, both sectors contributed 7.3 percent of total gross value added and in 1988 7.4 percent of total employment. A declining trend is similarly observed in employment growth rates between 1980 and 2000. Here again we see the adverse impact of increased openness on employment and overall productivity.

Lim and Bautista (2002) note the employment elasticity (or Okun’s elasticity)11 for the whole period under review was perverse — though output increased by 45 percent, unemployment increased by 1.8 percent as well. With an increasing output, unemployment should have been eased substantially. The authors sum up the employment and labor productivity effects of increased external liberalization:

- From 1988 to 2000, the bust periods displaced labor but the growth periods had very little employment absorption resulting to a long-run trend for the unemployment rate to rise.

- The lack of employment absorption in the growth periods had to do with: (a) lack of business confidence in some of the periods, (b) the need to improve labor productivity in the tradable (manufacturing) sector due to the higher exposure to external competition, (c) a high import dependence that biases against using domestic resources and inputs.

- Labor productivities in most economic sectors fall during recessions and increase during boom times. The series of growth and recessions, corresponding increases and decreases in labor productivities, as well as periods of confidence and non-confidence, have resulted not only in the lack of long-run growth in output, but also in the lack of improvement of labor productivities of the economic sectors as well as the unemployment rate over time.

- In the nineties, the services sector exhibited stronger labor absorption capacity and increasing share in output and employment, which may be due to its relative insulation from competitive forces unleashed in the external liberalization processes. Nonetheless, the falling and/or lagging labor productivities in this sector contributed to the lack of improvement in overall labor productivity.

Clearly, the alarmingly employment problem in the Philippines in a regime of increased openness challenges the very core of the “jobs claims” model of increased liberalization.

Increased External Liberalization and Declining Real Wages

Neoclassical economists are quick to argue that domestic price movements (that is, cheaper products due to tariff cuts on imported inputs) would fully offset the negative impact of tariff cuts on the terms of trade, leaving the overall effect on relative wages among trading countries almost negligible. Thus Saito and Tokutsu (2006: 24) assert that producers facing a fall in input prices as a result of tariff reduction would increase production by hiring additional less-skilled labor; this therefore has a positive effect on the wage gap. The authors go further by saying that “the positive effects on the wage gap through changes in tradable input prices seem substantially larger than those through changes in nontradable input prices.”

Here again is a case of simplification of assumptions using “general equilibrium” theoretical models which are often far from reality. Firstly, Saito’s and Tokutsu’s argument is biased against tradables and nontradables with high import content, low value-added (since an important part of the value-added goes to repatriation of profits), and the goods and services produced are partly sold in domestic markets. Moreover, oligopolistic market structures which are believed to be strong in the non-food manufacturing sectors are not built in equilibrium models, so that tariff reduction does not automatically translate into lower domestic and consumer prices. Given this constellation, the reality is thus unemployment, deindustrialization, and rising external deficits.

Destruction of Wage Anchors

According to Herr (2006), globalization in recent decades makes functional wage policy more difficult due to exchange rate fluctuations because “strong medium-term exchange rate movements create price level shocks which make it difficult to realize the wage norm. A strong depreciation in a country with a high import quota pushes up the domestic price level to such an extent that real wages fall to unacceptable levels.” The imminent threat of relocation of production to other countries forces workers to accept wage restraints or other cost-cutting measures.

Many employers are still wedded to the microeconomic logic that cutting costs increases international competitiveness. Thus, employers under stiff international competition push hard for wage increases below the functional wage norm.12 In some cases, unions even support low wage increases or accept wage cuts to save jobs. However, as Herr (2006) emphasizes, “employees and unions in such industries are in a weak position as wage increases below the wage norm destroy jobs.”

In Keynesian thinking, there is a relationship between wages and the price level, and nominal wages are the anchor of the level of prices. Thus higher wage costs (due to increased unit-labor costs) lead to higher prices. However, when nominal wage rate increases at the same percentage as productivity, unit-labor costs do not change and have neither an inflationary nor a deflationary effect. A functional wage policy, particularly in developed countries, should thus be anchored on a wage norm expressed in the following (Herr, 2006):

Increase in nominal wages per hour = trend productivity growth + target inflation rate

According to Herr (2006), wage development anchored on a wage norm releases monetary policy (or the central bank) from the fight against inflation. If a wage-price spiral commences in an inflationary direction, the central bank must slow down growth through restrictive monetary policy, i.e. increasing interest rates. Increasing interest rates induces producers to cut production eventually resulting in unemployment. More importantly, the nominal wage anchor serves as a “crucial dyke against cumulative deflation” so that “If this dyke breaks and nominal wages start to fall, a deflationary wage spiral and a deflationary demand constellation will stimulate each other and lead to a cumulative deflationary process” (Herr, 2006). The microeconomic logic that falling wages would enhance a company’s national and international competitiveness led Japan, characterized by its firm-based wage negotiations, to adopt a dysfunctional wage policy based on wage reductions at the end of the 1980s. The result was deflation that followed a prolonged period of stagnation.

In the case of developing countries with weak domestic currencies (and the role of imported goods in the consumption basket), the exchange rate is used as an index for domestic prices including wages. Wage development and money supply follow exchange rate movement. Nominal depreciations increase import prices and domestic cost levels, thus pushing inflation up. As higher prices reduce real wages, it is very likely that workers will demand an increase in nominal wages. A series of devaluations will thus trigger a wage-price spiral. Herr and Priewe (2001) point out, the higher the inflation, the higher the likelihood of devaluation. In such a situation, a country is caught in a devaluation-inflation spiral combined with a wage-price spiral. Thus, as Herr (2006) stresses, in developing countries, the exchange rate becomes an additional important nominal anchor of the price level; without the exchange rate anchor the wage anchor cannot function.

The fall in union membership and weakening of collective bargaining power of unions in many parts of the developed world has led to the destruction of nominal wage anchors. The result is not only detrimental to the developed countries but to the developing countries as well. Wage restraints and wage flexibility contributed to slow growth and stagnation in many developed countries which, according to some studies, was among the major causes of stagnation in the developing world particularly in the period 1980-2000. In this light, a restoration of the nominal wage anchor would augur well to the developing countries.

Wage and Distribution Effects of External Liberalization

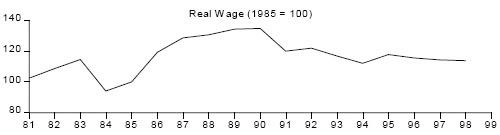

Determining the impact of external liberalization on the incomes of skilled and unskilled labor requires accurate and regularly available wage data. Unfortunately, there is a high scarcity of official wage data in Philippine labor statistics. Moreover, they are not generated regularly. Nonetheless, Figure 5 shows the pattern of real wages in the Philippines during the globalization decades of 1980 to 2000, a telling example of how increased frequency and depth of bust-recovery cycles (see Figure 1) could wreak havoc on wages. Note that while real wages were climbing after the 1983-1985 crisis, a gradual decline ensued in the 1990s.

Figure 5

Source: Lim and Bautista (2002).

After categorizing various occupations into three classes, namely professionals and managers, skilled and middle-level workers, and low-skilled workers using mean quarterly earnings as bases, Lim and Bautista (2002) note a noticeable decline in the percentage of low-skilled workers (from 84.2% in 1988 to 80.7% in 2000), simultaneous with increases in the percentages of both middle-level workers (from 12.0% in 1998 to 14.24% in 2000) and professionals and managers (from 3.8% in 1988 to 5.1% in 2000). The authors attribute this moderate shift to the likely shifts of employment across sectors rather than changes in the composition of skilled and unskilled workers within sectors. The movement of low-skilled labor out of agriculture and the traditional exportable sector would reduce the composition weights of low-skilled workers. This movement out of agriculture significantly contributed to the large drop in the share of household operating surplus over time (from 54.3% in 1982 to 39.7% in 2000).

According to the same authors, the small shift from low-skilled workers to middle-level workers, managers, and professionals may imply a deteriorating trend in the income distribution within labor. The general fall in real wages in the 1990s (see Figure 5) may imply a fall in wages for the majority of low-skilled labor since more than 80 percent of the employed labor force belong to this category of workers.

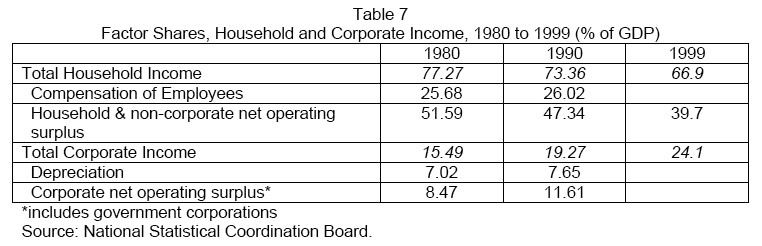

Lim and Bautista (2002) likewise note that while the share of net operating surplus of households and non-corporate entities started to decline beginning in the late eighties when liberalization began to intensify until 2000, a rise in the share of corporate income was observed during the same period (Table 7). Though having temporary declines during recessions (1985, 1991, 1998), corporate income’s share grew fast in the late eighties and mid-nineties.

The services sector has become the employment sink for a non-labor absorptive (or labor surplus) economy such as the Philippines. Note that a high degree of informality characterizes this sector. As this sector increases its share in output and employment, it contributes to the decline in real wages and lagging labor productivities. This trend, in turn, makes the total informal wage bill fall in relation to the formal economy.

Clearly, the combination of increased frequency and depth of boom-bust or recession-recovery cycles with rapid liberalization has not improved employment generation, labor productivities, and factor income distribution in the globalizing period 1980-2000.

Conclusions: What Next? Some Policy Challenges

There are crucial factors for an economy to reap potential economic benefits from external trade and liberalization: (1) export products with high technological content (high value added) located in growing global markets; (2) creation of domestic linkages of these exports; (3) capacity to capture a share of value added in international production networks; (4) attracting greenfield FDI that is anchored to the domestic economy; (5) coherent industrial or production sector strategies that promote industrialization and/or support structural transformation of economies (macroeconomic policies, investments in physical infrastructure, incentives and support for innovation, protection of infant industries, selective policies targeting specific sectors or firms); and (6) timing and speed of liberalization (gradual integration is preferred over a big bang or premature approach). Unfortunately, these factors have been wanting in the in the Philippines.

Using the Philippines as a country study, this paper adds up to the emerging growth literature challenging the causal link between trade liberalization and economic growth. In fact, the Philippine’s dismal economic performance during the decades of increased openness through rapid liberalization in 1980-2000 only brought stagnation and even negative growth in real per capita GDP, unemployment, and declining real wages.

So what are we to do?13

The Need for a Comprehensive Employment-oriented Industrial Strategy

Mere output growth should not continuously sidetrack the country from the more pressing need of a comprehensive approach to development that puts people at the core of development. This means that coherent and legitimate industrial policies and strategies should focus not only on price stability but on sources of real stability such as employment, wages, and poverty reduction and elimination. An employment-oriented growth strategy ensures that new jobs are created in pace with new entrants to the labor force. Issues of equity should also be addressed so that the benefits of growth are widely shared.

Coherent industrial policies and strategies should likewise promote structural transformation of the economy from commodity production and shallow integration (through mere assembly manufacturing) to the production of industrial products. As the UN (2006:83) emphasizes, developing countries need “to build up domestic capabilities to promote new sectors, either independently or in association with foreign capital.”

The Functional Wage Policy Complement

A functional wage policy should complement an employment-oriented production strategy. In the case of developing countries like the Philippines, an incomes policy should establish a productivity-oriented wage development. According to Herr (2006), an incomes policy has the function to reduce the competition between different groups of workers and prevent a dysfunctional race for a higher income share within the working class. However, this kind of incomes policy would work better in a set-up of centralized wage bargaining on a national level. In this light, unions should continue to push for a centralized form of wage bargaining.

In the Philippines where unions are weak and bargaining is done at the enterprise level, enforced minimum wages covering all industries are important to stabilize the price level. They set a floor for nominal wage cuts thus preventing a deflationary wage-price spiral (Herr, 2006). As a rule, minimum wages should not be much lower than the wage level of the least paid groups of workers so that they could be combined with any wage structure. Moreover, minimum wages have to be adjusted in an inflationary situation.

But where would a cash-strapped debt-ridden country like the Philippines get the initial resources to implement a comprehensive development strategy?

The answer is debt relief.

Debt Relief without Conditionality

In 2006, the Philippines’ external debt stood at 62.8 billion US dollars. In the same year, external debt as a proportion of exports recorded at 86.2 percent, while external debt service as a proportion of exports was 20 percent (Deutsch Bank Research, 2007). Clearly, the country’s external debt standing eats up a large portion of the country’s revenues, money that should have gone to more pro-growth programs.

The Philippines may consider negotiating for debt relief in an expanded HIPC (highly indebted poor countries) program. Without debt relief, the country will never be able to meet the basic needs of its people or make the necessary investments to undertake structural transformation of the economy.14 As Stigliz (2006:227) succinctly puts it, “any dollar sent to Washington or London or Bonn is a dollar not available for attacking poverty at home.” It should be emphasized however that debt relief should not be another occasion for holding the country to ransom; there should be no conditionality attached to the relief.

As a corollary, the country may negotiate for debt forgiveness for “odious debts” — debts that were immorally secured by past authoritarian regimes and corrupt political leadership. Creditors should share the blame for non-payment of odious debts because they should have known in the first place that such debts incurred by these regimes run the risk of not being paid. Stiglitz (2006:230) in fact cites what Argentinean Foreign Minister Drago pointed out a hundred years ago:

. . . there is no court of law that can force countries to repay; and if there is a broad consensus in the international community that a particular debt is odious and that the country has no obligation to repay it, then there are unlikely to be adverse consequences, there will be no incentive to repay.

Highly-indebted poor countries are often threatened with trade sanctions should they consider debt default or repudiation. However, Stiglitz (2006:230) notes that “trade sanctions are often ineffective, because trade with the sanctioned countries is profitable, so firms always try to circumvent the sanctions.”

Preferential Treatment for Developing Countries in Global Trade Policy

Although policy space in today’s global trade policy environment has been reduced15 by recent WTO rules and agreements, some forms of government intervention are still compatible to WTO rules. The UN (2006:85) cites some examples:

Duty free provisions can be maintained, as well as certain forms of export assistance, including public export credits . . . countries may continue to subsidize specific sectors until a complaining country presents evidence of material damage.

Infant industry and balance-of-payments protection are still permitted under the World Trade Organization but are subject to additional procedural requirements. Infant industry protection provisions, however, have not been invoked by any country since 1967, most likely because they entail compensation to injured parties.

Nonetheless, governments in developing countries and global social movements (including unions) should continuously push for more flexibility and public policy space for the adoption of industrial policies that promote diversification of production and technological upgrading in developing countries. Moreover, developing countries should give more attention “to rules that support the development of infant export industries, as well as the links between the dynamic export sector and other domestic activities and thus domestic market integration” (UN, 2006:86). These issues may be addressed in the context of the definition of special and differential treatment for developing countries in multilateral trade agreements.

Indeed, developing countries should be treated differently. Stiglitz (2006) advocates for an extended market access proposal for the poor countries where rich countries would simply open up their markets to poorer countries without reciprocity and without economic and political conditionality. Meanwhile, “middle income countries should open up their markets to the least developed countries, and should be allowed to extend preferences to one another without extending them to the rich countries, so that they need not fear that imports from those countries might kill their nascent industries” (Stiglitz, 2006: 83).

The Role of Unions

The road to recovery and development may seem arduous and the tasks at hand gargantuan. What is evident is that political commitment of national leadership is crucial in the pursuit of a more people-oriented development strategy. As a membership-based democratic social movement and an agency for workers’ voice and social justice, the union’s role becomes all the more important in putting people at the core of the development agenda. This calls for a more sustained and concerted labor action that is focused on community and solidarity.

In the realm of economic policy-making, unions should support any kind of initiative that would weaken the power of asset owners, i.e. Tobin tax, turn-over tax in the stock market, stable exchange rates, selective capital controls. Policies that expand the domestically-linked nontradables sector should likewise merit union support.

There have been successful initiatives where unions together with other social movements were able to expand public policy space and resist anti-people economic programs. On October 31, 2004, voters in Uruguay approved by a two-thirds margin the world’s first constitutional reform outlawing the outsourcing of water to the private sector. On December 15, 2004, Indonesia’s Constitutional Court came out with a landmark decision outlawing Law No. 20/2002 privatizing the country’s electrical system. The law was part of an agreement imposed by the WB in a $242.6 million loan granted to Indonesia in October 2003 (Shorrock, et al, 2005). These initiatives have been mounted by social movements in these countries and trade unions were at the core of these mobilizations. As O’Brien (2000:554) points out, “If the goal of social movements is to construct a world that balances liberal economic priorities with egalitarian values, such an aim only stands a chance of being accomplished if workers’ organisations play a large part in the struggle.”

Clearly, in confronting the global capital offensive, trade unions need to revitalize their organizations by building new alliances with the best parts of the movement, i.e. in the public sector, in transport, in some of the private service sectors, etc. Building networks of workers in the same industry across both national and company borders is also necessary to confront transnational corporations. To Wahl (2004), the development of an international, class-based solidarity in which democratic control of production and distribution is taken to the fore is crucial in the struggle against the neoliberal assault. Wahl also sees the need to build alliances with the new radical and militant global movement against neoliberalism in order to break with their illusions of class compromise.

Indeed, a progressive trade union strategy also entails challenging the dominant thinking of the trade union bureaucracy on the trade union purpose. New and difficult discussions and analyses within the movement have to be made and people’s anxiety and discontent should be politicized and channeled into trade union and political class-based struggles for their working and living conditions (Wahl, 2004).

1 Paper presented in the International Conference on “Labour and the Challenges of Development,” 1-3 April 2007, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, convened by the Global Labour University. The paper draws much from an on-going study entitled “Of Jobs Lost and Wages Depressed: The Impact of Trade Liberalization on Employment and Wage Levels in Two ASEAN Countries” by the same author. The other ASEAN country is Indonesia which is not yet included in this paper. The study will be completed in June 2007.

2 University Extension Specialist, School of Labor and Industrial Relation, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City 1101, Philippines. The author is a graduate of the International Master Program on Labour Policies and Globalisation, Global Labour University (University of Kassel and Berlin School of Economics), 2005-2006.

3 For a discussion and analysis of each of these episodes, see Lim and Bautista (2002).

4 Akyuz (2005) argues that there is no one-to-one correlation and that trade orientation of a country depends not only on its trade policies but also on other factors such as economic size, geographical features, and natural resource endowment.

5 Coined by Easterly (2001a) in his paper entitled “The Lost Decades: Developing Countries’ Stagnation in Spite of Policy Reform 1980-1998.”

6 See UN (2006:62).

7 TOT is the ratio of price of exports to the price of imports. When the number is falling, the country is said to have deteriorating terms of trade.

8 According to Akyuz (2005), the manufacturing value-added of G-7 countries as a whole consistently exceeded manufactured exports, while the opposite was the case for the leading export manufacturers in the South. While developing countries achieved a steeply rising ratio of manufactured exports to GDP between 1980 and 1997, this was not accompanied by a strong upward trend in the ratio of manufacturing value-added to GDP. Thus, the increase in the share of developing countries in world manufacturing exports has not been accompanied by a concomitant increase in their shares in world manufacturing value-added.

9 HT manufactures include complex electrical and electronic (including telecommunications) products, aerospace, precision instruments, fine chemicals, and pharmaceuticals. The Philippines’ HT manufactures are in electronics involving final processes with simple technologies and where low wages are an important competitive factor.

10 Nordas (2004) points out for example that imported intermediate inputs account for 35 percent of textile exports of the Philippines, the highest among the textile-exporting countries in the ASEAN.

11 Okun’s Law or employment elasticity states that the elasticity of the ratio of actual to potential output relative to a change in employment rate is a constant of roughly 3. Okun observed in the U.S. GNP in the 1950-1960s that a 1% rise in unemployment was associated with a 3% decrement in the ratio of actual GNP to full capacity GNP.

12 Increase in nominal wages per hour = trend productivity growth + target inflation rate.

13 A phrase popularized by the novel Fontamara by Ignazio Silone. London: Redwoods, 1994, p. 177.

14 In 1999, the country’s debt was already external 65% of GDP.

15 In the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations (1986-1994), the “single undertaking” approach replaced the code approach. This means that developing countries were no longer given the choice to opt out of certain agreements. See UN (2006:84).

Bibliography

Akyüz, Yilmaz. (2005). “Trade, Growth and Industrialization: Issues, Experience and Policy Challenges.” Third World Network. Accessed on 30 January 2007.

Cororaton, Caesar B. (2003). “Analyzing the Impact of Philippine Tariff Reform on Unemployment, Distribution and Poverty Using CGE-Microsimulation Approach.” Discussion Paper Series No. 2003-15. Philippine Institute of Development Studies, October.

De Dios, Emmanuel. (1998). “Philippine Economic Growth: Can It Last?”, in D. Timberman (editor). The Philippines, New Directions in Domestic Policy and Foreign Relations. USA: Asia Society; cited in Lim and Bautista (2002).

Deutsch Bank Research. (2007). Key Economic Indicators: Philippines. Accessed on 27 February 2007.

Dowrick, Steve and Jane Goley. (2004). “Trade Openness and Growth: Who Benefits?” Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 20.

Easterly, William R. (2001a). “The Lost Decades: Developing Countries’ Stagnation in Spite of Policy Reform 1980-1998.” Accessed on 2 February 2007.

Easterly, William R. (2001b). Global Development Network Growth Database. Accessed on 2 February 2007.

Herr, Hansjorg. (2002). “Wages, Employment and Prices — An Analysis of the Relationship Between Wage Level, Wage Structure, Minimum Wages and Employment and Prices.” Working Paper No. 15. June, Berlin School of Economics, Berlin.

Herr, H and J. Priewe. (2001). “The Macroeconomic Framework for Povery Reduction.”

Keynes, J. M. (1937) “The General Theory of Employment.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 47, pp. 209-223.

Lim, Joseph Y. and Carlos C. Bautista. (2002). “External Liberalization, Growth and Distribution in the Philippines.” Paper presented for the international conference on “External Liberalization, Growth, Development and Social Policy,” January 18-20, 2002, Melia Hotel, Hanoi, Vietnam.

National Statistics Office. (2002). Annual Survey of Philippine Business and Industry. Accessed on 22 February 2007.

Nordas, Hildegunn Kyvik. (2004). “The Global Textile and Clothing Industry post the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing.” Discussion Paper No. 5. Geneva: World Trade Organization.

Ranney, David C. and Robert R. Naiman. (1997) Does ‘Free Trade’ Create Good Jobs? A Rebuttal to the Clinton Administration’s Claims. Chicago: The Great Cities Institute, January.

Reyes, Romeo A. (2005). “Are Jobs Being Created or Lost in AFTA?” Jakarta Post. 31 May 2005.

Saito, Mika and Ichiro Tokutsu. (2006). “The Impact of Trade on Wages: What If Countries Are Not Small?” IMF Working Paper WP/06/155. International Monetary Fund.

Shorrock, Tim, Peter Bakvis and Molly McCoy. (2005). “Rolling Back the Bank: Case Studies of Successful Trade Union Resistance and Alternatives to the Policies of International Financial Institutions.” Draft unpublished paper. International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU).

Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2006). Making Globalization Work. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, Inc.

Tran Van Tho. (2002). AFTA in the Dynamic Perspective of Asian Trade. JCER Discussion Paper No. 77. Tokyo: Japan Center for Economic Research, April, p. 7.

Tussie, Diana and Carlos Aggio. (Undated). “Economic and Social Impacts of Trade Liberalization.” Accessed on 19 February 2007.

United Nations. (2006). World Economic and Social Survey 2006 — Diverging Growth and Development. Geneva: United Nations Economic and Social Affairs. Page 23 of 23

U.S. Department of State-Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs. (2006). Background Note: Philippines, October. Accessed on 22 February 2007.

Wahl, Asbjorn. (2004). “European Labor — The Ideological Legacy of the Social Pact.” Monthly Review. January, pp. 37-49.

Weisbrot, Mark, Dean Baker, Egor Kraev and Judy Chen. (2001). “The Scorecard on Globalization 1980-2000: Twenty Years of Diminished Progress.” Center for Economy and Policy Research (CEPR), July 11.

The paper in PDF is available at the Web site of the Global Labour University. It is reproduced here for educational purposes.

|

| Print