Lotteries, now run by most of our 50 states, are disguised forms of taxation that fall most heavily on those least able to pay. In today’s economic crisis, state leaders face rising resistance to taxation from everyone. Therefore, many of them plan to expand lotteries even more, hoping that no one realizes they represent a kind of masked tax. In the elegant words of conservative South Carolina State Senator Robert Ford, reported by the Associated Press, “Gambling ain’t no blight on society.” To fight them, we need first to expose state lotteries as disguised and very unfair taxation.

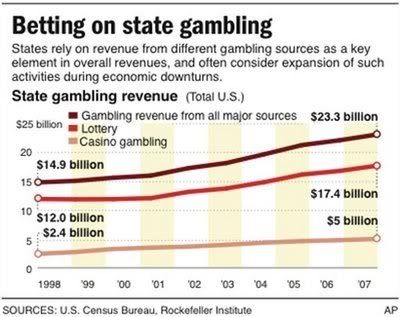

Consider the rising importance of state lottery revenues also documented in that Associated Press story:

Both Republicans and Democrats have been moving steadily toward ever more lottery sales; there is no reason to doubt that they will continue.

Where do lottery revenues come from? A famous recent study by Cornell University researchers reached these conclusions:

. . . lotteries are extremely popular, particularly among low income citizens. . . . [I]ndividuals with lower incomes substitute lottery play for other entertainment. . . . [L]ow income consumers may view lotteries as a convenient and otherwise rare opportunity for radically improving their standard of living. . . . [T]he desperate may turn to lotteries in an effort to escape hardship. We . . . find a strong and positive relationship between sales and poverty rates. . . .

In another study, Duke University researchers in 1999 found that the more education one has the less one spends on lottery tickets: dropouts averaged $700 annually compared to college graduate’s $178; and that those from households with annual incomes below $25,000 spent an average of nearly $600 per year on lottery tickets, while those from households earning over $100,000 averaged $289; blacks spent an average of $998, while whites spent $210.

Put simply, lotteries take the most from those who can least afford them. Thus, still another study of state lotteries concluded: “We find that the implicit tax is regressive in virtually all cases.” Instead of taxing those most able to pay, state leaders use lotteries to disguise a regressive tax that targets the middle and even more the poor. Just as the richest were getting much richer from 2001 to 2006, the middle and poor were getting ever more heavily taxed by means of lotteries.

How do states use their lottery revenues? Some 50-70 percent go to the winners; 20-40 per cent go to pay for states’ public services (often education) and the rest (10-20 per cent) go for “expenses” of running lotteries. In 2006, over half of California’s lottery receipts used for these “expenses” were paid as commissions to retailers for selling lottery tickets. Sales per retail outlet in 2006 averaged $188,000 in California (and $405,000 in New York). For many retailers across the country, profits from the fully automated selling of lottery tickets significantly boost their bottom lines.

Lotteries actually redistribute wealth from the poorer to the richer. The vast majority of middle-income and poor people buy tickets and win nothing or nearly nothing, while a tiny number of winners become wealthy. Lotteries raise ever more money for states from their middle-income and poor citizens rather than those most able to pay, thereby allowing the rich to escape rising taxes. Retail merchants get state welfare in profitable commissions on lottery sales. Politicians boast that they “did not raise taxes” — having raised money instead by lottery ticket sales.

The effects of lotteries in today’s economic crisis are even more perverse. Lotteries take huge sums from masses of people who would otherwise likely have spent that money on goods and services whose production gave people jobs. The lotteries then distribute over half that money to a few, suddenly enriched, individuals who likely will not spend as much (and thus generate fewer jobs). This is the exact opposite of the kind of economic stimulus a depressed economy needs. Yet many states are now planning increases in lottery sales to raise money “in these bad times.”

Lotteries are also powerful ideological and political weapons. They reinforce notions that individual acts — buying lottery tickets — are appropriate responses to society’s economic problems. Lotteries help to distract people from collective action to solve the economic crisis by changing society. Lotteries’ massive advertising shows an audacity of hype: shifting people from hope for the social fruits of collective action to hope for the personal fruits of individual gambling.

Finally, compare lotteries (disguised taxes) with taxes not wearing masks. Taxes raise money that mostly goes to fund states’ provision of public services. Lottery revenues make a few winners wealthy at the expense of the mass of taxpayers; only small portions of lottery revenues fund states’ services. We can socially target taxes to tap those most able to pay; we cannot do that with lotteries. Taxes can enable the states to provide public education, child and elderly care, public transportation and so on without using state employees to push us to gamble more, which is what lotteries do.

The issue here is not gambling per se; the point is not to engage the religious, moral, or mental health debates over gambling. Rather, what matters is the cynical use of state lotteries to disguise unfair tax burdens even as they worsen the economic crisis.

As an alternative to lottery expansions, states could together pass a property tax levied on property in the form of stocks and bonds. (See my earlier MRZine piece on property taxes: “Evading Taxes, Legally.”) Let’s recall that many states already tax property in the form of land, homes, commercial and industrial buildings, automobiles, and business inventories. There is no justification for excluding stocks and bonds from the property tax; stocks and bonds are the form in which the richest among us hold most of their property. A property tax on stocks and bonds could raise far more than lotteries do, it would tax those most able to pay, and it would end the injustice of allowing owners of stocks and bonds to avoid the taxes now levied on the other sorts of property most Americans own (cars, homes, etc.).

Rick Wolff is a Professor Emeritus at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst and also a Visiting Professor at the Graduate Program in International Affairs of the New School University in New York. He is the author of New Departures in Marxian Theory (Routledge, 2006) among many other publications. Be sure to check out the video of Rick Wolff’s lecture “Capitalism Hits the Fan: A Marxian View”: <vimeo.com/1962208>.